Key Takeaways

- Definition: A Bluetooth Access PCB is the central control unit integrating Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) modules with authentication logic to manage physical entry.

- Critical Metric: Impedance control (typically 50Ω) is the single most important factor for RF signal integrity and range.

- Power Management: For battery-operated units, quiescent current must be minimized (often <5µA) through careful component selection and sleep-mode logic.

- Interference: Proper grounding and shielding are essential to prevent noise from nearby

RFID Access PCBorQR Code Access PCBmodules. - Material Selection: Standard FR4 is often sufficient for BLE (2.4GHz), but tight tolerance control is required for the antenna matching network.

- Validation: Functional testing must include RSSI (Received Signal Strength Indicator) verification, not just connectivity checks.

- Manufacturing: APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory) recommends specific surface finishes like ENIG to ensure flat pads for fine-pitch RF components.

What and 2.4GHz (BLUETOOTH) Access PCB really means (scope & boundaries)

Understanding the core definition is the first step before diving into technical metrics. A Bluetooth Access PCB is not simply a printed circuit board with a Bluetooth chip; it is a specialized Access Management PCB designed to handle secure credentials, decrypt signals from mobile devices, and actuate locking mechanisms.

In modern security ecosystems, this board rarely operates in isolation. It often serves as the "master" controller that interfaces with a Keypad Access PCB for PIN entry or an RFID Access PCB for legacy card support. The scope of a Bluetooth Access PCB includes the RF front end (antenna and matching network), the microcontroller unit (MCU) for encryption, power management circuits, and the driver interfaces for electric strikes or magnetic locks.

The boundary of this technology lies in its dual requirement: it must be a robust radio frequency (RF) device and a secure logic controller. Unlike a standard consumer Bluetooth speaker, a Bluetooth Access PCB requires industrial-grade reliability, anti-tamper features, and often, weather-resistant design for outdoor deployment.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once the scope is defined, we must quantify what constitutes a high-quality board. The following metrics determine the success of a Bluetooth Access PCB in the field.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical range or influencing factors | How to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Impedance | Mismatched impedance causes signal reflection, reducing range and increasing power usage. | 50Ω ±10% (Standard for BLE antennas). | TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry) on test coupons. |

| RSSI Consistency | Ensures the "unlock distance" is predictable for the user (e.g., phone in pocket vs. holding phone). | -50dBm to -90dBm depending on distance. Variance should be <3dB. | Anechoic chamber testing or controlled environment functional test. |

| Quiescent Current | Critical for battery life in wireless smart locks. | 1µA to 10µA in sleep mode. | High-precision multimeter or power analyzer during sleep cycles. |

| Dielectric Constant (Dk) | Affects the speed of the signal and the width of impedance traces. | 4.2 to 4.6 (FR4). Stability over frequency is key. | Material datasheet verification and stackup simulation. |

| Thermal Dissipation | High-power regulators or motor drivers can heat up the board, affecting RF oscillator stability. | Max temp rise <20°C above ambient. | Thermal imaging camera under full load (lock actuation). |

| ESD Protection | Users touch the device constantly; static discharge can kill sensitive RF chips. | ±8kV Contact, ±15kV Air (IEC 61000-4-2). | ESD gun simulation on exposed interfaces. |

Selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

Metrics provide the data, but the application environment dictates which metrics to prioritize. Below are common scenarios for Bluetooth Access PCB deployment and the necessary design trade-offs.

1. Battery-Powered Residential Smart Lock

- Priority: Ultra-low power consumption.

- Trade-off: Reduced RF transmission power to save energy.

- Design Focus: Use latching relays to avoid constant current draw. Minimize LEDs.

2. High-Traffic Commercial Office Reader

- Priority: Speed and durability.

- Trade-off: Higher power consumption is acceptable (usually wired power).

- Design Focus: Robust thermal management for continuous operation. Integration with Security Equipment PCB standards for fire alarms.

3. Outdoor Gate Controller

- Priority: Environmental resistance and range.

- Trade-off: Larger physical size for protective conformal coating and higher gain antennas.

- Design Focus: Waterproofing, UV-resistant materials, and temperature-stable oscillators.

4. High-Security Server Room

- Priority: Encryption and Anti-Tamper.

- Trade-off: Higher cost due to multi-layer boards with buried vias for security meshes.

- Design Focus: Physical tamper detection circuits and secure element (SE) chips.

5. Multi-Modal Access Terminal

- Priority: Coexistence of signals.

- Trade-off: Complex layout to prevent interference between BLE, NFC, and

QR Code Access PCBcameras. - Design Focus: Strict shielding cans and physical separation of antenna blocks.

6. Invisible/Hidden Reader (Behind Drywall)

- Priority: Maximum RF penetration.

- Trade-off: Directionality is sacrificed for omnidirectional power.

- Design Focus: High-gain external antenna connectors (U.FL/IPEX) rather than PCB trace antennas.

From design to manufacturing (implementation checkpoints)

After selecting the right scenario, the design must move into production without losing fidelity. APTPCB uses the following checkpoints to ensure the design intent survives the manufacturing process.

1. Stackup Verification

- Recommendation: Define the layer stackup early to fix the distance between the RF trace and the reference ground plane.

- Risk: If the manufacturer changes the prepreg thickness, the 50Ω impedance will fail.

- Acceptance: Approve the manufacturer's stackup report before etching.

2. Antenna Keep-Out Area

- Recommendation: Ensure all copper (ground, power, signals) is removed from all layers directly beneath the PCB antenna.

- Risk: Copper below the antenna acts as a shield, killing the signal range immediately.

- Acceptance: Visual inspection of Gerber files and Antenna PCB guidelines.

3. Ground Via Stitching

- Recommendation: Place ground vias along the edges of RF transmission lines (via fencing).

- Risk: Lack of shielding allows external noise to couple into the Bluetooth signal.

- Acceptance: Check via spacing (typically <1/20th of wavelength).

4. Power Supply Decoupling

- Recommendation: Place capacitors as close as possible to the BLE SoC power pins.

- Risk: Voltage ripples can modulate the RF carrier, causing frequency drift.

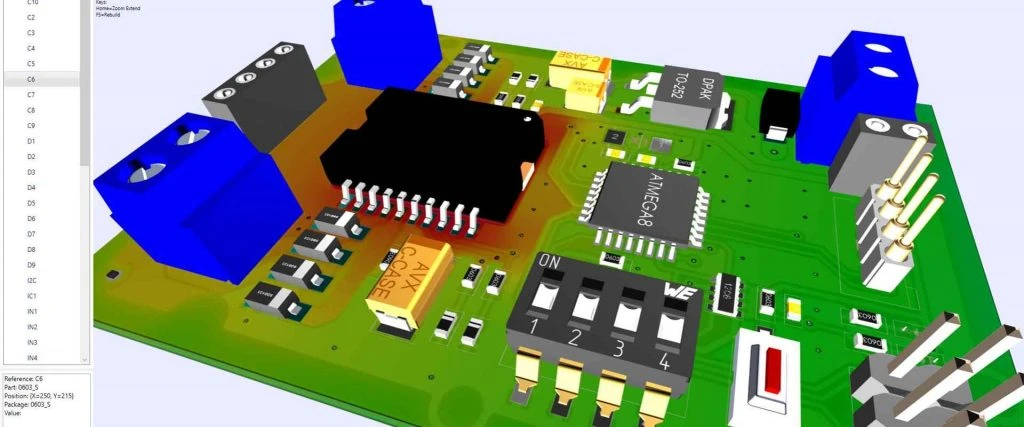

- Acceptance: Review placement in 3D viewer or assembly drawing.

5. Surface Finish Selection

- Recommendation: Use ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold).

- Risk: HASL (Hot Air Solder Leveling) is too uneven for small RF components and fine-pitch QFN packages.

- Acceptance: Specify ENIG clearly in fabrication notes.

6. Crystal Oscillator Layout

- Recommendation: Keep the crystal very close to the IC with a dedicated ground island.

- Risk: Parasitic capacitance on crystal lines prevents the Bluetooth radio from starting up.

- Acceptance: Design Rule Check (DRC) for trace length and isolation.

7. Test Point Access

- Recommendation: Add test points for UART/SWD and power rails, but keep them off RF lines.

- Risk: Stubs on RF lines create reflections.

- Acceptance: Verify test points are on DC lines only.

8. Panelization Strategy

- Recommendation: Use V-score or mouse bites that do not stress the antenna area during separation.

- Risk: Mechanical stress can crack ceramic baluns or lift antenna pads.

- Acceptance: Review panel drawing for stress relief near sensitive components.

9. Solder Mask Definition

- Recommendation: Use LDI (Laser Direct Imaging) for precise mask alignment.

- Risk: Mask encroaching on pads causes poor soldering of QFN chips.

- Acceptance: Check solder mask expansion rules (typically 2-3 mils).

10. Component Sourcing

- Recommendation: Validate availability of specific RF inductors and capacitors.

- Risk: Substituting RF passives with "generic" equivalents changes the resonant frequency.

- Acceptance: Lock the BOM (Bill of Materials) for critical RF parts.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a checklist, specific errors frequently occur in Bluetooth Access PCB layouts. Avoiding these pitfalls saves costly revision cycles.

1. The "Floating Ground" Error

- Mistake: Using a weak or broken ground plane under the RF section.

- Correction: The layer immediately below the RF trace must be a solid, unbroken ground reference. Do not route other signals through this reference plane.

2. Ignoring the Enclosure

- Mistake: Tuning the antenna perfectly in open air, then putting it inside a plastic or metal housing.

- Correction: The enclosure detunes the antenna. Leave a matching network (Pi-network) placeholder on the PCB to tune the antenna after the board is inside the final casing.

3. Noisy Power Routing

- Mistake: Routing the DC-DC converter switch node near the Bluetooth antenna.

- Correction: Keep switching power supplies at the opposite end of the board from the RF section. Use a Turnkey Assembly provider who understands component placement for noise reduction.

4. Wrong Trace Width for Stackup

- Mistake: Calculating trace width based on generic FR4 data (Dk 4.5) but manufacturing with a material that has a Dk of 4.2.

- Correction: Ask APTPCB for the specific material parameters before starting the layout.

5. Metal near the Antenna

- Mistake: Placing a battery, mounting screw, or USB connector right next to the chip antenna.

- Correction: Follow the manufacturer's datasheet for "clearance" zones strictly. Metal detunes the antenna and blocks radiation.

6. Overlooking Mobile Access Integration

- Mistake: Designing only for Bluetooth and forgetting the NFC requirements for

Mobile Access PCBfunctionality. - Correction: If the device supports Apple Wallet or Android NFC, ensure the NFC loop antenna does not magnetically couple destructively with the BLE antenna.

7. Poor Thermal Relief on Ground Pads

- Mistake: Connecting ground pads of the BLE module to the plane without thermal relief spokes.

- Correction: While solid connections are good for RF, they cause cold solder joints during reflow. Use thermal reliefs or ensure the reflow profile is adjusted for high thermal mass.

FAQ

Q: Can I use standard FR4 material for Bluetooth Access PCBs? A: Yes, standard FR4 is acceptable for 2.4GHz Bluetooth applications. However, you must control the stackup height and trace width precisely to maintain 50Ω impedance. For higher performance, materials with tighter dielectric tolerance are preferred.

Q: What is the difference between a Bluetooth Access PCB and a standard BLE module?

A: A standard BLE module is just the radio. A Bluetooth Access PCB includes the module plus the security logic, power regulation, lock drivers, and interfaces for other readers like Keypad Access PCB units.

Q: How do I test the range of my PCB during manufacturing? A: You cannot test full range on a production line. Instead, use a "Golden Unit" comparison or a wired RF test to verify the output power (TX) and sensitivity (RX) are within limits.

Q: Why is my Bluetooth range short when the board is installed? A: This is often due to the enclosure (casing) or mounting surface. Mounting a reader on a metal door frame can severely detune the antenna. You may need a spacer or a specialized ferrite sheet.

Q: Does APTPCB support firmware flashing for these boards? A: Yes, we support IC programming as part of the assembly process. You provide the hex/bin file and the checksum for verification.

Q: How do I prevent someone from hacking the Bluetooth signal? A: Security is handled at the firmware and protocol level (e.g., AES-128 encryption). However, the PCB must support "Secure Element" chips and have tamper-detection circuits to prevent physical bypassing.

Q: Can I combine RFID and Bluetooth on the same PCB? A: Yes, this is common. However, the 13.56MHz (RFID) and 2.4GHz (Bluetooth) antennas must be carefully placed to avoid interference.

Q: What is the lead time for a Bluetooth Access PCB prototype? A: Standard lead time for bare boards is typically 3-5 days. For full assembly including component sourcing, it is usually 2-3 weeks depending on component availability.

Related pages & tools

- Antenna PCB Design: Deep dive into RF layout rules.

- Security Equipment PCB: Industry-specific standards for access control.

- Turnkey PCB Assembly: How we handle the entire production process.

- Impedance Calculator: Tool to estimate trace widths for 50Ω lines.

Glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) | A power-conserving variant of Bluetooth technology used for IoT and access control. |

| Impedance Matching | The practice of making the source and load resistance equal (usually 50Ω) to maximize power transfer. |

| RSSI | Received Signal Strength Indicator. A measurement of the power present in a received radio signal. |

| Balun | A component that converts balanced signals (from the chip) to unbalanced signals (for the antenna). |

| Trace Antenna | An antenna structure etched directly into the PCB copper, saving cost compared to ceramic chips. |

| Chip Antenna | A small ceramic component used as an antenna, saving space but requiring a specific ground clearance. |

| EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) | Unwanted noise or signals that disrupt the function of the PCB. |

| NFC (Near Field Communication) | A short-range wireless technology often paired with Bluetooth for Mobile Access PCB solutions. |

| Wiegand Protocol | A legacy wiring standard used to connect card readers to access controllers. |

| OSDP (Open Supervised Device Protocol) | A more secure, bi-directional communication standard replacing Wiegand. |

| GPIO | General Purpose Input/Output pins on the MCU used to control LEDs, buzzers, and relays. |

| DFM (Design for Manufacturing) | The engineering practice of designing PCB products in such a way that they are easy to manufacture. |

| SoC (System on Chip) | An integrated circuit that integrates all components of a computer or other electronic system (e.g., Radio + MCU). |

Conclusion (next steps)

The Bluetooth Access PCB is the bridge between digital credentials and physical security. Whether you are designing a standalone smart lock or a complex networked reader, success depends on balancing RF performance, power efficiency, and robust mechanical design.

To move from concept to production, APTPCB requires the following data for a comprehensive DFM review and accurate quote:

- Gerber Files: Including all copper layers, drill files, and outline.

- Stackup Requirements: Specify your desired finished thickness and impedance control lines (e.g., 50Ω on Layer 1).

- BOM (Bill of Materials): Highlight any critical RF components (baluns, crystals, antennas) that must not be substituted.

- Test Requirements: Define if you need firmware flashing or functional RSSI testing.

By addressing these details early, you ensure your access control product is secure, reliable, and ready for the market.