Electronic reliability often hinges on what you remove from the board, not just what you place on it. Cleaning after soldering is the critical process of removing flux residues, handling oils, and manufacturing debris to prevent electrical failure. While some manufacturers rely on "no-clean" processes to cut costs, high-reliability sectors cannot afford the risk of electrochemical migration or parasitic leakage. At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we understand that a clean board is the foundation of a durable product. This guide covers the entire spectrum of cleaning, from selecting the right chemistry to validating cleanliness standards.

Key Takeaways

- Flux is the primary target: The main goal is removing active flux acids that can cause corrosion or dendritic growth over time.

- "No-clean" is a misnomer: Even no-clean fluxes can leave residues that attract moisture or interfere with conformal coating adhesion.

- Ionic contamination is the metric: Visual inspection is not enough; you must measure invisible ionic residues using ROSE or SIR testing.

- Component compatibility matters: Not all components (e.g., unsealed buzzers or switches) can withstand high-pressure water or solvent washes.

- Process validation is mandatory: A cleaning process must be validated against specific industry standards like IPC-J-STD-001.

- APTPCB prioritizes reliability: We tailor the wash process based on the specific flux type and end-use environment of the PCBA.

What cleaning after soldering really means (scope & boundaries)

Understanding the takeaways above requires defining the core process and why it is physically necessary. Cleaning after soldering is not merely an aesthetic choice; it is a chemical neutralization and removal process. During soldering, flux is used to remove oxides from metal surfaces to ensure a good intermetallic bond. However, the residues left behind—whether rosin-based, water-soluble, or synthetic—can become conductive or corrosive if exposed to humidity.

The scope of cleaning extends beyond just wiping the board. It involves three distinct phases:

- Solvation: Using a chemical agent (solvent or water with saponifiers) to dissolve the flux residue.

- Rinsing: Removing the dissolved flux and the cleaning agent itself to prevent redeposition.

- Drying: Removing all moisture, as trapped water can be just as dangerous as the flux itself.

If these steps are not executed correctly, the board may suffer from Electrochemical Migration (ECM). This occurs when an electric field is applied across two conductors in the presence of moisture and ionic contamination, causing metal dendrites to grow and eventually short the circuit.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once you understand the scope and risks, you must establish quantifiable metrics to measure the success of the cleaning process. Visual cleanliness is subjective; reliability requires data.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical range or influencing factors | How to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Contamination | Measures conductive ions left on the board that could cause shorts. | < 1.56 µg/cm² NaCl equivalent (historical IPC limit). Modern high-rel often requires < 0.75 µg/cm². | ROSE Test (Resistivity of Solvent Extract). |

| Surface Insulation Resistance (SIR) | Measures the electrical resistance between conductors under heat and humidity. | > 100 MΩ (Megaohms) typically. Higher is better. | SIR Testing (Comb patterns tested in a humidity chamber). |

| Visual Cleanliness | Ensures no gross residues, solder balls, or white scaling are present. | IPC-A-610 Class 2 or 3 criteria. No visible residue at 10x-40x magnification. | Microscope Inspection (AOI or Manual). |

| Surface Energy (Dyne Level) | Critical for conformal coating adhesion. High surface energy means better wetting. | > 40 dynes/cm is usually required for good coating adhesion. | Dyne Pens (Ink test). |

| Flux Residue Weight | Quantifies the physical amount of residue remaining. | Specific to the flux datasheet and process window. | Gravimetric Analysis. |

Selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

Metrics define success, but the actual cleaning method you choose depends heavily on your specific application and constraints. Different industries and board designs dictate different cleaning strategies.

1. High-Reliability (Aerospace, Medical, Automotive)

- Context: Failure is not an option. Long service life in harsh environments.

- Method: Aqueous cleaning with saponifiers or vapor degreasing.

- Trade-off: High cost and process time. Requires strict validation.

- Why: Ensures removal of all ionic species to prevent latent failures.

- APTPCB Note: For medical PCB applications, we recommend full wash cycles regardless of flux type.

2. Consumer Electronics (Cost-Sensitive)

- Context: Short product lifecycle, controlled environment (office/home).

- Method: No-Clean Flux (leave-on).

- Trade-off: Residue remains. Lower reliability in humid conditions. Harder to coat later.

- Why: Eliminates the washing step, reducing manufacturing cost and throughput time.

3. RF and High-Frequency Circuits

- Context: Signal integrity is paramount.

- Method: High-precision solvent cleaning.

- Trade-off: Complex chemical handling.

- Why: Flux residues act as dielectrics, altering impedance and causing signal loss at high frequencies.

4. Conformal Coating Preparation

- Context: The board will be coated for protection.

- Method: Thorough cleaning and drying (baking).

- Trade-off: Adds cycle time for baking.

- Why: Residues prevent the coating from sticking (delamination), creating pockets where moisture collects.

5. Water-Soluble Flux Assembly

- Context: Aggressive flux used for difficult soldering (e.g., oxidized pads).

- Method: Inline aqueous wash (hot DI water).

- Trade-off: Must be washed immediately after reflow.

- Why: Water-soluble fluxes are highly corrosive and will eat copper traces if left for hours.

6. Rework and Hand Soldering

- Context: Manual modification or repair.

- Method: Localized solvent cleaning (brush/swab).

- Trade-off: Risk of spreading residue rather than removing it.

- Why: You cannot easily wash the whole board again if sensitive components are attached.

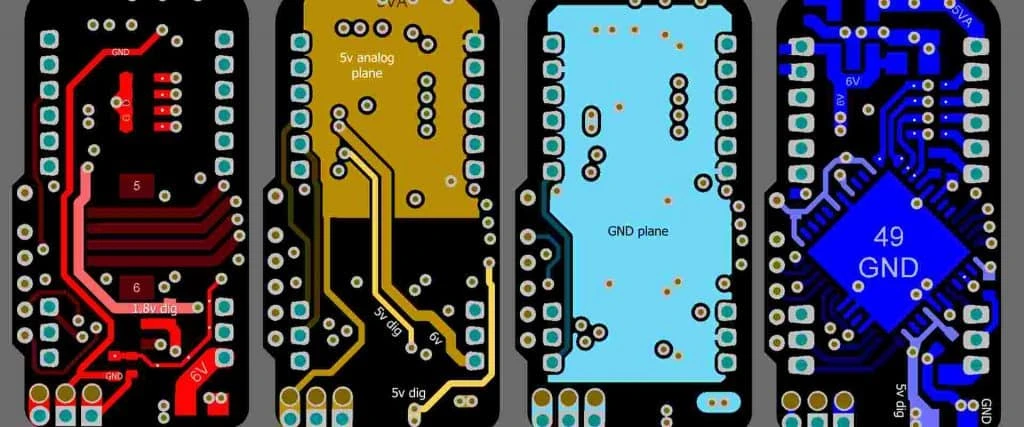

From design to manufacturing (implementation checkpoints)

Selecting a scenario is theoretical; executing it requires a structured process that starts at the design phase and continues through assembly. Here are the critical checkpoints for implementing a robust cleaning strategy.

1. Component Standoff Height

- Recommendation: Ensure components (especially BGAs and QFNs) have sufficient standoff height.

- Risk: Low standoff prevents cleaning fluid from flowing under the part, trapping flux.

- Acceptance: Design review confirms clearance or specifies low-surface-tension cleaning agents.

2. Component Compatibility

- Recommendation: Identify "non-washable" parts (buzzers, open switches, humidity sensors) in the BOM.

- Risk: Water intrusion destroys these components.

- Acceptance: Mark these for "install after wash" or use protective masking.

3. Flux Selection

- Recommendation: Match the flux type (Rosin, OA, Synthetic) to the cleaning chemistry.

- Risk: Using water to clean rosin flux without a saponifier results in white, sticky residue.

- Acceptance: Chemical compatibility test.

4. Reflow Profile Optimization

- Recommendation: Ensure the reflow profile does not "char" the flux.

- Risk: Overheated flux polymerizes and becomes concrete-hard, making it impossible to clean.

- Acceptance: Thermal profiling verification.

5. Wash Temperature and Pressure

- Recommendation: Set water temperature (typically 60°C) and spray pressure to penetrate gaps.

- Risk: Too low = residue remains; Too high = component damage.

- Acceptance: Inline spray pressure monitoring.

6. Rinse Quality (DI Water)

- Recommendation: Use Deionized (DI) water for the final rinse.

- Risk: Tap water introduces new minerals (calcium, magnesium) onto the board.

- Acceptance: Resistivity meter on the rinse tank (> 10 MΩ-cm).

7. Drying Process

- Recommendation: Use air knives followed by a thermal bake.

- Risk: Flash drying leaves moisture under components, leading to "popcorning" or corrosion.

- Acceptance: Weight test or humidity indicator cards.

8. Cleanliness Testing Frequency

- Recommendation: Perform ROSE testing on a sample basis (e.g., 1 per batch).

- Risk: Process drift goes unnoticed until field failures occur.

- Acceptance: Logged test results in the quality report.

9. Stencil Design for Cleaning

- Recommendation: Adjust aperture reduction to limit excess flux volume.

- Risk: Too much paste leaves excessive flux that is harder to remove.

- Acceptance: SMT/THT process inspection (SPI).

10. Handling After Cleaning

- Recommendation: Operators must wear gloves immediately after the wash.

- Risk: Finger oils (salts) re-contaminate the clean surface.

- Acceptance: Strict ESD and handling protocols.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a solid plan, specific operational errors can derail the cleaning process and compromise the PCB.

- Mixing Flux Chemistries:

- Mistake: Using a water-soluble flux for wave soldering and a no-clean flux for hand soldering on the same board.

- Correction: Standardize flux types or ensure the cleaning agent is compatible with both.

- "No-Clean" Means "Don't Clean":

- Mistake: Attempting to clean "no-clean" flux with pure water. This turns the clear residue into a white, conductive mess.

- Correction: If you must clean "no-clean" flux, use a chemical saponifier designed for it.

- Ignoring Thermal Shock:

- Mistake: Plunging a hot board directly from reflow into cold cleaning solvent.

- Correction: Allow the board to cool to a safe temperature to prevent ceramic capacitor cracking.

- Insufficient Under-Component Cleaning:

- Mistake: Assuming high pressure cleans under large BGAs.

- Correction: Use "tilt" spray jets or Z-axis ultrasonic cleaning (if safe for components) to ensure fluid exchange under the die.

- Reusing Dirty Solvent:

- Mistake: Saturation of the cleaning bath leads to redeposition of flux onto the board.

- Correction: Monitor the specific gravity or contamination level of the solvent and cycle it regularly.

- Poor Hand Solder Best Practices:

- Mistake: Technicians flooding the area with liquid flux during rework, making it impossible to spot-clean effectively.

- Correction: Use flux pens for precise application and clean immediately while the residue is soft.

- Neglecting Rinse Water Quality:

- Mistake: Using standard tap water for rinsing.

- Correction: Always use closed-loop DI water systems to ensure no mineral deposits are left behind.

FAQ

1. Can I use Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) for all cleaning? IPA is effective for many rosin-based fluxes but struggles with synthetic or water-soluble residues. It also evaporates quickly, which can cool the board and attract condensation if not managed.

2. Is ultrasonic cleaning safe for all components? No. Ultrasonic vibrations can damage internal wire bonds in crystals, oscillators, and MEMS sensors. Always check component datasheets before using ultrasonic tanks.

3. What is the "white residue" often seen after cleaning? This is usually caused by the reaction between rosin flux and water (saponification failure) or the polymerization of flux due to excessive heat. It can also be lead salts if the cleaning agent is too aggressive.

4. How soon after soldering should I clean? Ideally, within minutes. As flux cools and ages, it hardens and becomes significantly more difficult to dissolve.

5. Do I need to clean if I am not coating the board? For consumer electronics using no-clean flux, usually no. For industrial, automotive, or medical boards, yes—cleaning improves reliability regardless of coating.

6. How do I clean under a BGA? You need a cleaning system with low surface tension fluid and high-pressure spray jets directed at an angle. Soaking alone is rarely sufficient.

7. What are through hole soldering basics regarding cleaning? Through-hole joints often trap flux on the top side of the board (component side) as it travels up the barrel. Ensure your cleaning process addresses both top and bottom sides.

8. Can I clean a board that has a battery on it? Generally, no. Water or solvent can short the battery terminals or cause leakage. Batteries should be hand-soldered after the wash process or masked effectively.

9. What is the difference between saponifier and solvent? A solvent dissolves the flux directly. A saponifier reacts chemically with the flux (turning acids into soap) to make it water-soluble so it can be rinsed away.

10. How does APTPCB validate cleanliness? We use a combination of visual inspection (IPC-A-610) and ionic contamination testing (ROSE) to ensure every batch meets the specified cleanliness standards.

Related pages & tools

- SMT & THT Assembly Services: Learn how we integrate cleaning into our assembly lines.

- Medical PCB Manufacturing: Explore high-reliability standards where cleaning is mandatory.

- Get a Quote: Submit your design and specify your cleanliness requirements.

Glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Azeotrope | A mixture of solvents that boils at a constant temperature, ensuring the composition doesn't change during evaporation. |

| Cavitation | The formation of bubbles in a liquid (used in ultrasonic cleaning) that implode to scrub surfaces. |

| Dendrites | Fern-like metal growths caused by electromigration that can short-circuit adjacent conductors. |

| DI Water | Deionized water; water that has had almost all of its mineral ions removed. |

| ECM | Electrochemical Migration; the movement of metal ions under an electric field in the presence of moisture. |

| Flux | A chemical agent used to facilitate soldering by removing oxidation from metal surfaces. |

| Hydrophobic | Repelling water; some fluxes are hydrophobic and require solvents to remove. |

| Hygroscopic | Absorbing moisture from the air; some flux residues are hygroscopic and become corrosive. |

| IPA | Isopropyl Alcohol; a common solvent used for manual cleaning. |

| No-Clean Flux | Flux formulated to leave a benign, non-conductive residue that theoretically does not require removal. |

| ROSE Test | Resistivity of Solvent Extract; a test to measure the total ionic contamination on a PCB. |

| Saponifier | An alkaline chemical added to water to convert rosin/resin flux into a washable soap. |

| SIR | Surface Insulation Resistance; a measure of the electrical resistance between traces. |

| Standoff | The vertical distance between the component body and the PCB surface. |

| Surface Tension | The property of a liquid that allows it to resist external force; lower surface tension helps cleaning fluids enter tight gaps. |

Conclusion (next steps)

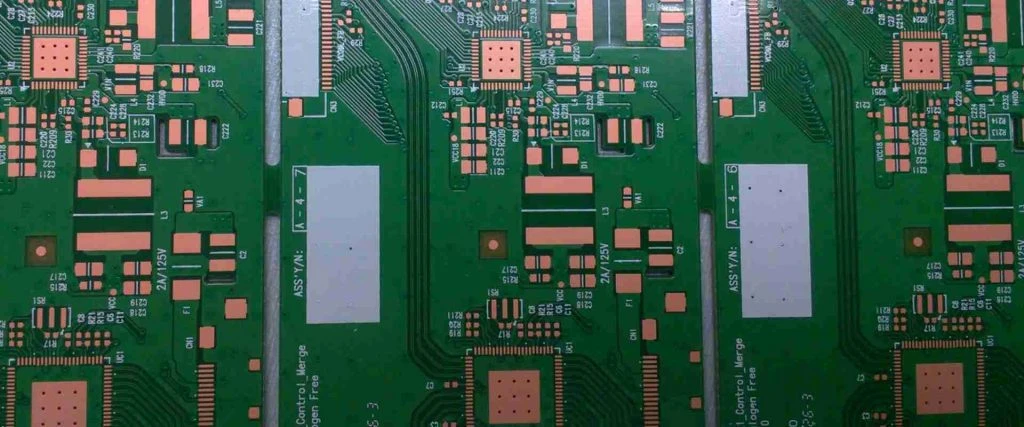

Cleaning after soldering is a vital step in the manufacturing lifecycle that dictates the long-term reliability of your product. Whether you are dealing with complex through hole soldering basics or high-density SMT components, the presence of active residues is a risk you cannot ignore. A robust cleaning strategy involves selecting the right flux, designing for washability, and validating the results with data.

At APTPCB, we ensure that your boards are not just visually clean, but chemically neutral and ready for the field. When you are ready to move your design into production, providing clear requirements helps us execute the perfect wash process.

For a DFM review or Quote, please provide:

- Gerber Files: To assess component density and standoff.

- Assembly Drawing: Highlighting non-washable components.

- Cleanliness Specs: Specific ionic contamination limits (if different from IPC standards).

- Flux Preference: If you have a specific requirement for water-soluble or no-clean chemistries.

Ensure your product's longevity by partnering with a manufacturer who understands the science of clean.