Engineers working in quantum computing, deep-space astronomy, and high-energy physics face a unique challenge: maintaining signal integrity while battling extreme thermal constraints. Differential microwave routing cryogenic design is the discipline of laying out high-frequency printed circuit boards (PCBs) that function reliably at temperatures ranging from 77 Kelvin down to millikelvin levels. Unlike standard room-temperature designs, these boards must balance electrical performance (low loss, matched impedance) with thermal isolation to prevent heat from overwhelming sensitive cryogenic stages.

At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we specialize in fabricating these complex interconnects where material properties shift drastically under cold conditions. This guide serves as a comprehensive resource for engineers moving from theoretical simulation to physical production.

Key Takeaways

- Definition: Differential microwave routing cryogenic refers to the layout of paired transmission lines carrying GHz-range signals in environments below -150°C, prioritizing noise rejection and thermal management.

- Material Physics: Dielectric constants ($D_k$) and loss tangents ($D_f$) change as temperatures drop; room temperature simulations often fail without cryogenic material models.

- Thermal vs. Electrical: There is an inherent trade-off between maximizing electrical conductivity (for signal) and minimizing thermal conductivity (to reduce heat load).

- Geometry Matters: Stripline configurations offer better shielding for dense qubit control lines but require careful via management to avoid resonance.

- Surface Finish: Avoid pure tin due to "tin pest"; Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold (ENIG) or Silver is preferred for cryogenic reliability.

- Validation: Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) signatures will shift from room temperature to operating temperature; designs must account for this delta.

What this topic means (scope & boundaries)

Understanding the core definition is the first step before diving into the specific metrics that govern performance.

Differential microwave routing cryogenic is not simply about taking a standard RF layout and freezing it. It involves a fundamental rethinking of how electromagnetic waves propagate through materials that are physically contracting and electrically altering. In a standard environment, a differential pair is used primarily for common-mode noise rejection. In a cryostat, this noise rejection is critical because signal levels are often incredibly low (single-photon or few-electron levels), and the environment is filled with pump noise and vibration.

The scope of this discipline covers three main physical phenomena:

- Kinetic Inductance: In superconducting traces, kinetic inductance becomes significant, altering the characteristic impedance of the line.

- Thermal Contraction: Different materials (copper, PTFE, epoxy) shrink at different rates (CTE mismatch), leading to stress fractures or delamination if the routing geometry is too rigid.

- Conductivity Changes: Copper resistance drops significantly (Residual Resistance Ratio - RRR), which changes the skin depth and insertion loss profile.

This type of routing is most commonly found in a cryostat feedthrough PCB, which acts as the bridge between room temperature electronics and the quantum processor or sensor at the mixing chamber stage.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once the scope is defined, engineers must quantify success using specific performance metrics that apply at low temperatures.

The following table outlines the critical parameters for evaluating a differential microwave routing cryogenic design.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical Range / Factors | How to Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Impedance ($Z_{diff}$) | Mismatches cause reflections, heating, and signal corruption. | Usually $100\Omega \pm 5%$. Note: $Z_0$ drops as substrates shrink and $D_k$ changes. | TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry) with cryogenic correction factors. |

| Heat Load (Thermal Conductivity) | Excessive heat flow can saturate the dilution refrigerator's cooling power. | Measured in $W/K$. Depends on trace cross-section and substrate material. | Thermal modeling software or physical heat flow measurement. |

| Insertion Loss ($S_{21}$) | Signal attenuation reduces the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). | $< 1 \text{dB/m}$ at operating freq. Improves at low temp due to lower conductor loss. | VNA (Vector Network Analyzer) transmission test. |

| Return Loss ($S_{11}$) | Indicates how much signal is reflected back to the source. | Target $< -20 \text{dB}$ across the bandwidth. | VNA reflection test. |

| Skew (Intra-pair) | Phase mismatch converts differential mode to common mode noise. | $< 5 \text{ps}$ (or $< 10 \text{mil}$ length mismatch). | TDR or high-speed oscilloscope. |

| Crosstalk (NEXT/FEXT) | High density routing leads to signal bleed between channels. | $< -50 \text{dB}$ required for quantum qubit control lines. | VNA multi-port measurement. |

| Outgassing Rate | Materials release gas in vacuum, compromising thermal isolation. | Must meet TML $< 1%$ and CVCM $< 0.1%$. | ASTM E595 testing standards. |

How to choose an approach (trade-offs by scenario)

Having established the metrics, the next challenge is selecting the right routing strategy for your specific application scenario.

Different stages of a cryostat require different approaches to differential microwave routing cryogenic design. Below are common scenarios and the recommended trade-offs.

1. The High-Density Quantum Interconnect

- Scenario: Routing hundreds of control lines to a quantum processor.

- Challenge: Space is limited; crosstalk is the enemy.

- Recommendation: Use Stripline routing on inner layers.

- Trade-off: Striplines require more layers and vias (increasing cost and thermal mass) but provide superior isolation compared to microstrips.

- APTPCB Tip: Use high-aspect-ratio vias to save space.

2. The Low-Noise Amplifier (LNA) Input

- Scenario: Carrying extremely weak signals from the sample to the first amplification stage.

- Challenge: Minimizing dielectric loss is paramount.

- Recommendation: Use Microstrip or Coplanar Waveguide (CPW) on the top layer with a low-loss PTFE substrate (e.g., Rogers 4000 series).

- Trade-off: Microstrips are more susceptible to radiation and crosstalk but eliminate the dielectric loss associated with the upper laminate in a stripline.

- Link: Explore our Microwave PCB capabilities for low-loss material options.

3. Flux Bias Line Design

- Scenario: Carrying DC currents combined with RF pulses to tune qubit frequencies.

- Challenge: Needs high isolation from readout lines; carries higher current.

- Recommendation: Use wider differential pairs with increased spacing (3W rule or greater).

- Trade-off: Consumes significant board real estate.

- LSI Context: Effective flux bias line design often requires twisted pair geometry emulation on the PCB or specialized filtering structures.

4. The Thermal Break (Interposer)

- Scenario: Bridging the 4K stage to the 10mK stage.

- Challenge: Blocking heat flow while passing RF signals.

- Recommendation: Use meandering traces (serpentine routing) to increase the thermal path length without affecting electrical length significantly (if matched). Use substrates with poor thermal conductivity (like Polyimide/Flex).

- Trade-off: Longer traces increase insertion loss.

- Link: Consider Rigid-Flex PCB solutions for thermal isolation.

5. High-Power Drive Lines

- Scenario: Sending strong microwave pulses to manipulate spins.

- Challenge: Dissipating heat generated by the RF power itself (dielectric heating).

- Recommendation: Use metal-backed PCBs or heavy copper layers for thermal sinking.

- Trade-off: Metal cores can affect impedance control and are harder to manufacture with fine pitch.

6. Superconducting Resonator Readout

- Scenario: Multiplexed readout of multiple resonators on a single feedline.

- Challenge: Maintaining exact impedance to avoid standing waves.

- Recommendation: Strictly controlled impedance with backdrilled vias to remove stubs.

- Trade-off: Backdrilling adds a process step and cost.

Implementation checkpoints (design to manufacturing)

After selecting the right scenario, you must execute the design and prepare it for fabrication without errors.

Successful differential microwave routing cryogenic implementation requires a rigorous checklist during the layout and CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) phases.

Material Selection: Choose materials with documented cryogenic properties. PTFE-based laminates (like Rogers RT/duroid) are standard. Avoid standard FR4 for signal layers below 77K due to unpredictable $D_k$ shifts, though it may be used for mechanical stiffeners.

- Check: Have you accounted for the Z-axis expansion coefficient?

- Link: Review Rogers PCB materials for specific data sheets.

Impedance Calculation Adjustment: Standard calculators assume room temperature. At 4K, substrates shrink (increasing capacitance) and conductors become more conductive.

- Action: Design for slightly higher impedance (e.g., 52 ohms) at room temp if the substrate shrinkage is expected to drop it to 50 ohms at 4K. Use our Impedance Calculator as a baseline, then apply cryogenic scaling factors.

Trace Geometry:

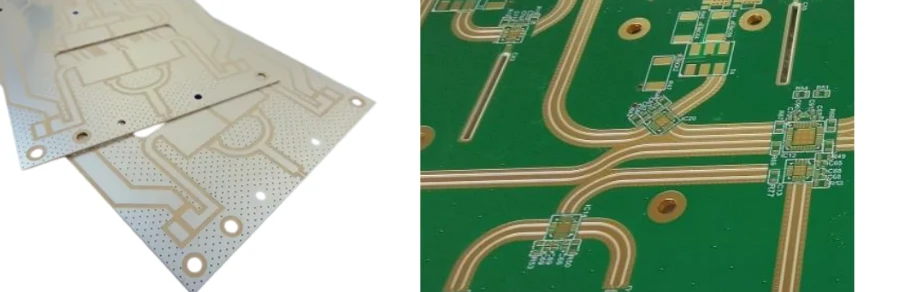

- Cornering: Use mitered 45-degree bends or, preferably, curved traces (arcs) to minimize reflections at microwave frequencies.

- Coupling: Maintain consistent gap spacing. Any separation in the differential pair creates an impedance discontinuity.

Via Design:

- Grounding: Place ground stitching vias close to signal vias to provide a continuous return path.

- Stubs: Remove unused via stubs using backdrilling. At 10GHz+, a small stub acts as a notch filter.

Thermal Relief vs. RF Performance:

- Conflict: RF prefers solid ground planes. Cryogenics prefers meshed planes to reduce thermal conductivity and prevent delamination.

- Resolution: Use hatched ground planes only if the mesh size is significantly smaller than the wavelength (usually $< \lambda/20$). Otherwise, use solid copper and rely on the substrate for thermal isolation.

Surface Finish:

- Requirement: Non-magnetic, wire-bondable, and reliable at cold temps.

- Selection: ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) is the industry standard. ENEPIG is also acceptable. Avoid HASL (uneven) and Immersion Tin (tin pest risk).

Connector Launch:

- Critical: The transition from the coaxial connector (SMP, SMA) to the PCB is the most common failure point.

- Action: Use a tapered launch geometry. Simulate the connector footprint in 3D EM software.

Solder Mask:

- Recommendation: Remove solder mask over high-frequency traces. Solder mask adds loss and its dielectric constant varies.

- Risk: Exposed copper can oxidize; ensure proper plating.

Fabrication Notes:

- Explicitly state: "Do not alter trace width for yield without approval."

- Specify: "Class 3 plating requirements" for via reliability under thermal cycling.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a checklist, engineers often fall into specific traps when dealing with cryogenic microwave signals.

Avoid these frequent errors to ensure your differential microwave routing cryogenic project succeeds on the first spin.

Mistake 1: Ignoring the "Skin Effect" change.

- Issue: At cryogenic temperatures, the skin depth decreases as conductivity increases. However, surface roughness becomes the dominant loss mechanism.

- Correction: Use "Reverse Treated" or "Very Low Profile" (VLP) copper foils. Standard copper roughness will cause unexpectedly high losses at low temps.

Mistake 2: Over-constraining the board.

- Issue: Bolting a PCB rigidly to a copper cold finger when the PCB shrinks less than the copper mount causes the board to bow or snap.

- Correction: Use slotted mounting holes or spring-loaded washers to allow for differential thermal contraction.

Mistake 3: Neglecting the connector CTE.

- Issue: Soldering a brass connector to a PTFE board. Brass shrinks more than PTFE, shearing the solder joints at 4K.

- Correction: Use connectors made of Kovar or stainless steel that match the expansion coefficient of the board, or use compliant pin connectors.

Mistake 4: Ground Loops in Differential Pairs.

- Issue: Breaking the ground reference plane under a differential pair.

- Correction: Ensure a solid, uninterrupted reference plane runs beneath the entire length of the differential pair. If crossing a split plane is unavoidable, use stitching capacitors (though this is risky in RF).

Mistake 5: Assuming "Lossless" Transmission.

- Issue: Assuming that because copper superconducts or has low resistance, loss is zero.

- Correction: Dielectric loss often dominates at microwave frequencies, even at 4K. The substrate choice is more critical than the conductor choice for loss budgets.

Mistake 6: Poor LSI Integration.

- Issue: Treating a cryostat feedthrough PCB as a simple wire harness.

- Correction: Treat the feedthrough as a complex filter. It must block room-temperature thermal noise while passing the signal.

FAQ (stackup, impedance, Dk/Df, lead time)

Q1: Does the dielectric constant ($D_k$) increase or decrease at cryogenic temperatures? Generally, $D_k$ increases slightly as the material cools and contracts (density increases), but this depends on the specific polymer or ceramic matrix. For PTFE, the change is often small but measurable.

Q2: Can I use FR4 for cryogenic microwave routing? For DC or low-frequency signals, yes. For microwave signals ($>1$ GHz), FR4 is too lossy and its properties are too inconsistent at 4K. Use Rogers or Taconic materials.

Q3: What is the best surface finish for cryogenic PCBs? ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) is the most robust. Soft gold allows for wire bonding, and the nickel barrier prevents copper diffusion.

Q4: How do I handle the thermal contraction mismatch between the PCB and the housing? Design the PCB with elongated mounting holes (slots) radiating from a fixed center point. This allows the board to shrink towards the center without stress.

Q5: Should I use microstrip or stripline for differential pairs? Use stripline if isolation and crosstalk are your main concerns (e.g., dense qubit lines). Use microstrip if minimizing loss and reducing layer count are prioritized.

Q6: What is the "tin pest" and why does it matter? Tin pest is an allotropic transformation of tin that occurs at low temperatures, causing the solder to turn into powder. Avoid pure tin finishes; leaded solder or specific lead-free alloys with additives prevent this.

Q7: How do I test a cryogenic PCB at room temperature? You cannot perfectly replicate 4K performance at 300K. However, you can correlate the data. If the return loss is poor at room temp, it will likely be poor at 4K. Impedance will shift, so aim for a target that accounts for the predicted shift.

Q8: What is the minimum trace width for cryogenic etching? APTPCB can achieve trace widths down to 3 mil (0.075mm) for standard processing, and finer for HDI applications. However, wider traces (5 mil+) are preferred for impedance consistency.

Q9: Do I need to remove the solder mask? For high-performance microwave signals ($>10$ GHz), yes. The solder mask adds dielectric loss and uncertainty. Use a "solder mask defined" approach only where necessary for assembly.

Q10: Can APTPCB manufacture PCBs with superconducting materials? Yes, we can process specialized laminates and coatings. Please contact our engineering team to discuss specific superconducting requirements (e.g., Niobium or Aluminum sputtering compatibility).

Related pages & tools

To further assist with your design, utilize these resources from APTPCB:

- Impedance Calculator: Estimate your trace dimensions before starting your layout.

- Microwave PCB Manufacturing: Detailed capabilities regarding high-frequency laminates and tolerances.

- Rogers PCB Materials: Specifications for the most common cryogenic-compatible substrates.

- Rigid-Flex PCB: Ideal solutions for vibration isolation and thermal breaks in cryostats.

- HDI PCB: High-density interconnects for compact quantum processor interfaces.

Glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Differential Pair | Two complementary transmission lines carrying equal and opposite signals to reject common-mode noise. |

| Cryostat | A device used to maintain extremely low temperatures (cryogenic), often using liquid helium or pulse tubes. |

| Feedthrough | A component (often a PCB) that passes signals from the outside (room temp) to the inside (vacuum/cold) of a chamber. |

| CTE (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion) | The rate at which a material expands or contracts with temperature changes. Critical for reliability. |

| Dielectric Constant ($D_k$) | A measure of a material's ability to store electrical energy in an electric field. Affects impedance and signal speed. |

| Loss Tangent ($D_f$) | A measure of signal power lost as heat within the dielectric material. |

| Skin Effect | The tendency of high-frequency alternating current to distribute itself near the surface of the conductor. |

| Stripline | A conductor sandwiched between two ground planes within a PCB. Offers excellent shielding. |

| Microstrip | A conductor on the outer layer of a PCB, separated from a single ground plane by a dielectric. |

| S-Parameters | Scattering parameters (S11, S21, etc.) describing the electrical behavior of linear electrical networks. |

| TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry) | A measurement technique used to determine the impedance and location of faults in a transmission line. |

| Flux Bias | A control signal (DC + RF) used to tune the frequency of superconducting qubits (SQUIDs). |

| Outgassing | The release of gas that was dissolved, trapped, frozen, or absorbed in some material. |

Conclusion (next steps)

Differential microwave routing cryogenic is a specialized field where the margin for error is measured in millikelvins and picoseconds. Success requires a holistic view that combines electromagnetic theory, material science, and thermal engineering. By understanding the metrics, selecting the right routing topology, and validating your design against manufacturing constraints, you can build robust interconnects for the next generation of quantum and deep-space technologies.

When you are ready to move from simulation to fabrication, APTPCB is here to help.

For a comprehensive DFM review and accurate quote, please provide:

- Gerber Files: RS-274X format preferred.

- Stackup Details: Specify material types (e.g., Rogers 4003C), copper weights, and dielectric thicknesses.

- Impedance Requirements: Clearly label differential pairs and target impedance (e.g., $100\Omega \pm 5%$).

- Operating Temperature: Let us know if this is for 77K, 4K, or mK environments so we can advise on surface finishes and materials.

- Testing Requirements: Specify if TDR reports or specific frequency sweep data is required.

Visit our Contact Page or Quote Page to start your project today.