Dynamic flex life cycle design focuses on engineering Flexible Printed Circuits (FPC) to withstand millions of bending cycles without electrical or mechanical failure. Unlike static "install-to-fit" applications, dynamic designs require specific material choices, trace geometries, and stackup configurations to manage stress accumulation in the copper grain structure.

Quick Answer (30 Seconds)

- Critical Rule: The bend radius should generally be at least 100 times the thickness of the copper conductor for high-reliability dynamic applications, or follow the 10:1 (1-layer) to 20:1 (2-layer) board thickness ratio.

- Common Pitfall: Placing vias or Plated Through Holes (PTH) within the dynamic bend zone causes immediate cracking; keep them at least 2.5mm away from the bend.

- Verification: Use IPC-TM-650 Method 2.4.3 (Flexural Fatigue) to validate the estimated cycle life before mass production.

- Boundary Case: If the application requires >100,000 cycles, standard Electro-Deposited (ED) copper is insufficient; you must specify Rolled Annealed (RA) copper.

- DFM Requirement: Always define the grain direction of the RA copper on the fabrication drawing; the grain must run parallel to the length of the circuit (perpendicular to the bend axis).

Highlights

- Strategies to position the neutral axis for maximum longevity.

- Differences between static and dynamic flex design requirements.

- Material selection guide: Polyimide (PI) vs. PET and RA vs. ED copper.

- Step-by-step calculation for bend radius ratios.

- Troubleshooting guide for common failures like work hardening and delamination.

- Best practices for stiffener design for FPC in dynamic environments.

- Glossary of essential terms for communicating with PCB fabricators.

Contents

- dynamic flex life cycle design: definition and scope

- dynamic flex life cycle design rules and specifications

- dynamic flex life cycle design implementation steps

- dynamic flex life cycle design troubleshooting

- How to choose dynamic flex life cycle design

- dynamic flex life cycle design FAQ

- dynamic flex life cycle design glossary

- Request a quote for dynamic flex life cycle design

- Conclusion

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design: Definition and Scope

Dynamic flex life cycle design is the engineering discipline of creating flexible circuits intended to bend, fold, or twist repeatedly during the product's operation. This differs fundamentally from static flex, where the circuit is bent once during assembly and remains stationary. The goal is to prevent fatigue failure in the copper conductors and the dielectric insulation.

Applies when:

- Hinge mechanisms: Laptops, flip phones, and wearable devices where the circuit bridges two moving parts.

- Sliding components: Printers, scanners, and optical disk drives where the print head moves back and forth.

- Robotics: Joint connections in robotic arms or automation equipment requiring continuous motion.

- Expansion loops: Automotive clock springs or steering column controls.

- Medical devices: Catheters or imaging equipment that must articulate during procedures.

Doesn’t apply when:

- Install-to-fit: The flex is bent only to fit inside the enclosure and never moves again.

- Vibration environments: While vibration causes stress, it is usually low-amplitude; this is treated as high-cycle fatigue but differs from the large-displacement bending of dynamic flex.

- Rigid-flex transition zones: If the bend is only for assembly clearance and is mechanically constrained by the housing.

- Standard rigid PCBs: Obviously, FR4 materials cannot sustain dynamic bending.

- Keypads: Membrane switches often use flex materials but rely on dome switches rather than bending the substrate itself.

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design Rules and Specifications

The following rules are critical for achieving high cycle counts. Ignoring these parameters often leads to conductor work hardening and eventual fracture.

| Rule | Recommended value/range | Why it matters | How to verify | If ignored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bend Radius Ratio (1 Layer) | > 100x Conductor Thickness (or 10x Board Thickness) | Reduces strain on the outer surface of the copper, keeping it in the elastic region. | Measure bend radius in CAD; check stackup thickness. | Copper cracks after few cycles. |

| Bend Radius Ratio (2 Layer) | > 150x Conductor Thickness (or 20x Board Thickness) | Two layers increase stiffness; higher ratio is needed to prevent shear failure. | Calculate ratio: $R / Thickness$. | Delamination or conductor fracture. |

| Copper Type | Rolled Annealed (RA) | RA copper has an elongated grain structure that resists fatigue better than ED copper. | Check material datasheet (IPC-4562 Grade 2). | Rapid fatigue failure (<10k cycles). |

| Grain Direction | Perpendicular to Bend Axis | Bending "with the grain" prevents cracks from propagating across the conductor. | Specify on Fab Drawing; visual inspection of raw sheet. | Reduced life cycle by 50-70%. |

| Conductor Routing | Perpendicular to Bend | Traces running at angles or parallel to the bend experience torsion and shear. | CAD Design Rule Check (DRC). | Trace lifting or twisting failure. |

| Neutral Axis Placement | Center of Stackup | The geometric center experiences zero tension and zero compression. | Stackup analysis software. | Uneven stress leads to warping/cracks. |

| I-Beam Effect | Avoid Stacking Traces | Traces on top and bottom layers directly over each other increase stiffness (I-beam). | Visual check of Top vs. Bottom layers. | Increased stiffness; earlier failure. |

| Coverlay Type | Polyimide (PI) Coverlay | Flexible solder mask is brittle compared to laminated PI coverlay. | Specify "Coverlay" in BOM, not "Solder Mask". | Insulation cracking and exposure. |

| Via Keep-out | > 2.5mm from Bend | Plated holes are rigid anchors that concentrate stress. | Set CAD keep-out zones. | Plating cracks; open circuits. |

| Trace Width Change | Gradual Teardrops | Sudden width changes create stress risers. | Visual inspection of routing. | Cracks at the transition point. |

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design Implementation Steps

Implementing a robust dynamic flex life cycle design requires a systematic approach during the layout phase.

Define Mechanical Constraints: Determine the exact bend radius, the angle of the bend (e.g., 90° vs. 180°), and the estimated number of cycles (e.g., 10k, 100k, 1M+). This dictates the material class.

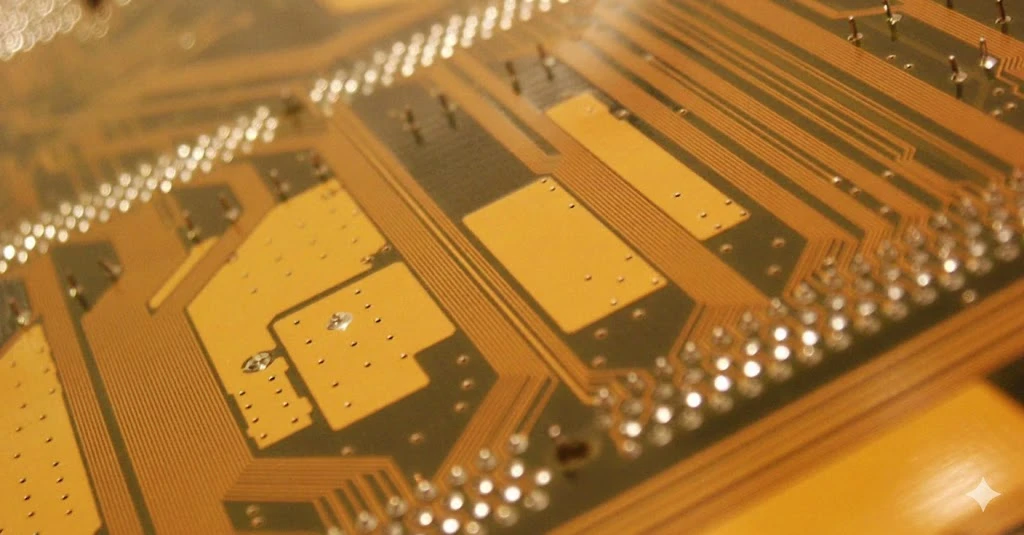

Select Materials (RA Copper & Polyimide): Choose a base material with Rolled Annealed (RA) copper. Avoid standard FR4-style prepregs. Use adhesive-less base materials if possible to reduce thickness and improve flexibility.

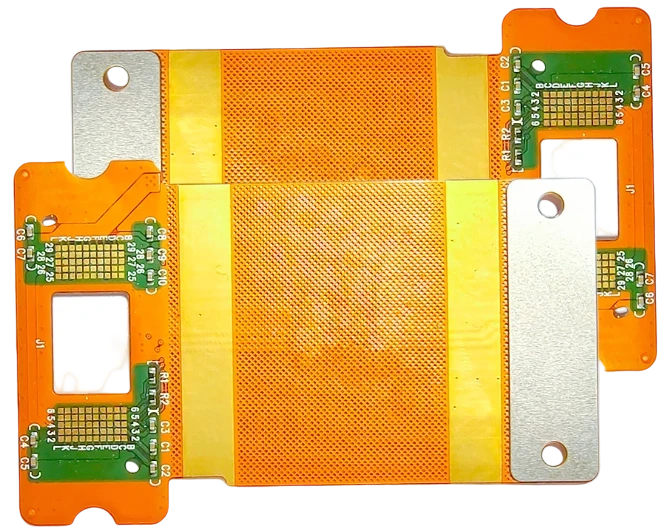

Calculate the Stackup (Neutral Axis): Design the stackup so the conductors are as close to the neutral axis as possible. For a single-layer dynamic flex, the conductor is naturally near the center if the base polyimide and coverlay polyimide are of equal thickness.

- Check: Is the stackup symmetrical?

Route Conductors Perpendicularly: Ensure all traces crossing the bend zone travel straight across (90° to the bend axis). If you must change direction, use large curved corners rather than sharp 45° or 90° angles.

Stagger Conductors (Double-Sided): If using a 2-layer flex, offset the top and bottom traces so they do not overlap. This prevents the "I-Beam" effect, which significantly increases stiffness and stress.

Design Coverlay and Stiffeners: Define the coverlay window design carefully. Ensure coverlay extends fully over the bend area without openings. Place stiffener design for FPC components (like FR4 or Polyimide stiffeners) strictly in the static areas to support connectors, ensuring they stop at least 1-2mm before the dynamic zone begins.

Add Tear Stops: Add copper features or slits at the edge of the flex circuit in the bend zone to prevent a small tear from propagating across the entire width of the cable.

Generate Fabrication Data: Include a note on the fabrication drawing: "Grain direction of RA copper to be parallel to the long axis of the circuit."

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design Troubleshooting

When dynamic flex circuits fail, they usually leave specific forensic evidence.

Symptom: Intermittent Open Circuits

- Likely Cause: Work hardening of the copper due to a bend radius that is too tight.

- Checks: Inspect the copper grain structure under a microscope. Look for micro-cracks running across the trace.

- Fix: Increase the bend radius or reduce the copper thickness (e.g., go from 1oz to 0.5oz).

- Prevention: Adhere strictly to the 100x conductor thickness rule.

Symptom: Insulation Cracking

- Likely Cause: Use of flexible solder mask instead of polyimide coverlay, or coverlay that is too thick.

- Checks: Check the BOM for material type. Verify coverlay thickness (usually 12.5µm or 25µm is preferred for dynamic).

- Fix: Switch to a thinner, laminated polyimide coverlay.

- Prevention: Avoid liquid photoimageable (LPI) solder masks in dynamic zones.

Symptom: Delamination (Blistering)

- Likely Cause: Shear forces between layers in a multi-layer stackup during bending.

- Checks: Look for separation between the copper and the base dielectric.

- Fix: Switch to a single-layer design ("unbonded" layers) where layers are allowed to slide over each other.

- Prevention: Use "air gap" or "loose leaf" construction for high-layer-count dynamic flex.

Symptom: Trace Lifting at Stiffener Edge

- Likely Cause: Stress concentration where the flexible part meets the rigid stiffener.

- Checks: Inspect the transition zone. Is there a bead of epoxy (strain relief)?

- Fix: Add an epoxy strain relief bead at the stiffener interface.

- Prevention: Ensure stiffener design for FPC includes a smooth transition and does not end exactly where the bend begins.

Symptom: Cracked Plating in Vias

- Likely Cause: Vias placed within the bend radius.

- Checks: Review CAD layout against the mechanical bend zone.

- Fix: Move vias to the static area.

- Prevention: Implement strict CAD keep-out zones for vias in dynamic areas.

How to Choose Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design

Making the right design decisions early saves costly iterations.

- If the cycle count is > 100,000: Choose Rolled Annealed (RA) copper. Do not use ED copper.

- If the bend radius is extremely tight (< 3mm): Choose a single-layer flex design. Multi-layer designs will likely fail due to thickness.

- If you need controlled impedance in a dynamic zone: Choose a cross-hatched ground plane instead of a solid copper pour. Solid planes are too stiff and will crack; cross-hatching retains flexibility.

- If the flex must carry high current: Choose wider traces rather than thicker copper. Thicker copper (e.g., 2oz) has a much lower fatigue life than wider 0.5oz copper.

- If the assembly requires component mounting near the bend: Choose a stiffener design for FPC that supports the component area but leaves a gap before the bend starts.

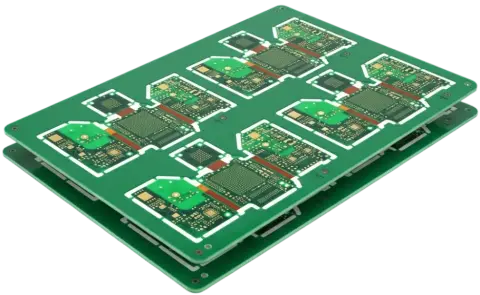

- If the flex is long and complex: Choose to panelize the design with the grain direction in mind, even if it reduces material utilization (yield).

- If you need to expose pads for ZIF connectors: Choose a coverlay window design that leaves the contact fingers exposed but ensures the coverlay encapsulates the trace roots to prevent lifting.

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design FAQ

What is the cost impact of using RA copper vs. ED copper? RA copper is generally 10-20% more expensive than standard ED copper due to the processing required to elongate the grain structure. However, for dynamic applications, this cost is negligible compared to the cost of field failure.

Can I use rigid-flex for dynamic applications? Yes, but the dynamic action must occur strictly in the flexible section. The rigid sections must remain static. The transition zone must be carefully designed with strain relief.

How do I test for dynamic flex life cycle? The industry standard is IPC-TM-650, Method 2.4.3. This involves a flexural fatigue tester that bends the sample around a specific radius mandrel for a set number of cycles while monitoring electrical continuity.

What is the "Neutral Axis" and why is it important? The neutral axis is the plane within the stackup where there is neither compression nor tension during bending. Placing conductors here minimizes stress. In a balanced stackup, this is the geometric center.

Is solder mask acceptable for dynamic flex? No. Standard LPI solder mask is too brittle and will crack. You must use Polyimide Coverlay (Kapton).

- See Flex PCB Materials.

What is the maximum number of layers for a dynamic flex? Ideally, 1 or 2 layers. If you need more layers, use "unbonded" construction where the inner layers are not glued together in the bend zone, allowing them to slide.

How does "coverlay window design" affect reliability? Improper windows can create stress risers. Windows should be used for termination pads only. Avoid "bikini" cuts (removing coverlay from large areas) in dynamic zones as it exposes traces to environmental damage and changes the mechanical stiffness abruptly.

What is the best surface finish for dynamic flex? ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) is common, but for the dynamic area itself, the copper should be covered by coverlay. The finish only applies to exposed pads. Soft Gold is preferred for contacts.

Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design Glossary

| Term | Meaning | Why it matters in practice |

|---|---|---|

| RA Copper | Rolled Annealed Copper. Copper foil treated to have an elongated horizontal grain structure. | Essential for high-cycle dynamic flexing; resists cracking better than vertical-grain ED copper. |

| ED Copper | Electro-Deposited Copper. Standard copper with a vertical grain structure. | Suitable for static flex or rigid boards; prone to fracture in dynamic applications. |

| Neutral Axis | The central plane of the material stackup that experiences zero stress during bending. | Conductors placed here last the longest. Deviating from this axis increases tensile or compressive stress. |

| I-Beam Effect | The structural stiffness created when top and bottom traces are stacked directly on top of each other. | Increases rigidity and stress. Staggering traces prevents this. |

| Coverlay | A laminate of polyimide and adhesive used to insulate flex circuits. | More flexible and durable than solder mask; required for dynamic zones. |

| Stiffener | A rigid piece of material (FR4, PI, Metal) laminated to the flex to support components. | Stiffener design for FPC is crucial to ensure the dynamic zone is isolated from the rigid connector area. |

| Grain Direction | The orientation of the copper crystals formed during the rolling process. | Traces must run parallel to the grain (perpendicular to the bend) to maximize life. |

| Service Loop | Extra length added to the flex circuit. | Allows for installation tolerances and reduces tension on the connectors during movement. |

| Springback | The tendency of the flex to return to its flat state after bending. | Affects assembly; dynamic designs must account for the force the flex exerts on the mechanism. |

Request a Quote for Dynamic Flex Life Cycle Design

When requesting a quote for a dynamic flex circuit, providing complete data ensures accurate pricing and a valid DFM review. We specialize in high-reliability flex and rigid-flex fabrication.

Please include the following in your RFQ package:

- Gerber Files: RS-274X or ODB++ format.

- Fabrication Drawing: Must specify "Dynamic Application" and "RA Copper".

- Stackup Diagram: Indicate layer order, copper weight, and coverlay thickness.

- Cycle Count Requirement: E.g., "Must withstand 1 million cycles at 5mm radius."

- Bend Radius: The minimum radius the part will experience in use.

- Stiffener Details: Drawings showing location and material (FR4, PI, SS) for stiffener design for FPC.

- Quantities: Prototype and production volumes.

Conclusion

Successful dynamic flex life cycle design is a balance of material science and geometry. By adhering to the 100x thickness rule, utilizing Rolled Annealed copper, and carefully managing the neutral axis, you can prevent premature field failures. Always validate your design with physical endurance testing before scaling to mass production.

For assistance with your next dynamic flex project, verify your stackup and design rules with our engineering team. We can help optimize your coverlay window design and ensure your stiffener design for FPC meets manufacturing standards.