High mass board thermal profiling is the critical process of managing heat absorption in heavy printed circuit boards during assembly. Unlike standard PCBs, high mass boards—characterized by thick copper layers, metal cores, or high layer counts—possess significant thermal inertia. This inertia causes them to heat up and cool down much slower than the components mounted on them. If the thermal profile is not carefully engineered, manufacturers face two opposing risks: cold solder joints on the heavy ground planes or overheated, damaged components on the surface.

This guide covers the entire workflow required to achieve a perfect solder joint on high thermal mass assemblies.

Key Takeaways

- Thermal Inertia: High mass boards absorb heat slowly; standard profiles will result in cold joints.

- Soak Zone Importance: A longer soak time is essential to equalize temperatures across the assembly before reflow.

- Delta T Management: The temperature difference between the hottest and coldest parts of the board must be minimized.

- Thermocouple Placement: Sensors must be placed on both the heaviest thermal mass and the most sensitive component.

- Validation: X-ray inspection and cross-sectioning are non-negotiable for verifying hidden solder joints.

- Material Specifics: Ceramic and metal core boards require distinct profiling strategies compared to FR4.

- Process Control: Consistent cleaning and surface preparation are prerequisites for successful wetting on high mass surfaces.

What high mass board thermal profiling really means (scope & boundaries)

Understanding the core definition of this process is the first step toward mastering the specific challenges of heavy PCB assembly.

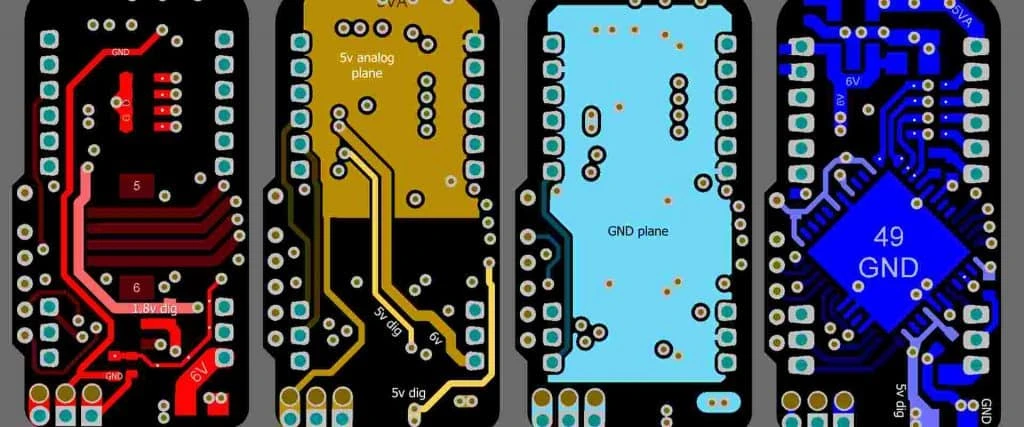

High mass board thermal profiling is the calibration of a reflow oven or wave soldering machine to accommodate PCBs with high thermal capacity. A "high mass" board typically includes features like heavy copper (3 oz to 20 oz), metal cores (aluminum or copper base), ceramic substrates, or high layer counts (20+ layers).

The primary challenge is the "thermal lag." When a high mass board enters the oven, the heavy copper planes act as heat sinks. They steal thermal energy from the solder pads. If the oven settings are based on a standard board, the solder paste on the heavy pads may never reach the liquidus temperature, even if the air temperature is correct. Conversely, if you simply crank up the heat to compensate, you risk frying sensitive surface-mount components before the board reaches reflow temperature.

At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we define successful profiling not just by melting solder, but by achieving a uniform thermal equilibrium across the entire assembly. This ensures that a tiny 0402 capacitor and a massive power transistor reflow simultaneously.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once the scope is defined, engineers must rely on specific, quantifiable metrics to judge the success of a thermal profile.

The following table outlines the critical data points required for high mass board thermal profiling.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical Range / Factors | How to Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soak Time | Allows the PCB core to catch up to the surface temperature. | 60–120 seconds (longer for higher mass). | Time spent between flux activation and reflow start (usually 150°C–200°C). |

| Ramp Rate (Up) | Controls thermal shock and flux evaporation. | 0.5°C to 2.0°C per second. Slower for ceramics. | Slope of the temperature curve during the heating phase. |

| Time Above Liquidus (TAL) | Determines the quality of the intermetallic bond. | 45–90 seconds. High mass boards often need the upper end. | Time the solder joint remains above the alloy's melting point (e.g., 217°C for SAC305). |

| Peak Temperature | Ensures full wetting without component damage. | 235°C–250°C. | The maximum temperature recorded by any thermocouple. |

| Delta T (ΔT) | Indicates thermal uniformity across the board. | <10°C is ideal; <15°C is acceptable for very high mass. | Difference between the hottest and coldest thermocouple at peak reflow. |

| Cooling Slope | Affects grain structure of the solder joint. | 2°C to 4°C per second. | Slope of the curve after peak temperature. |

Selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

With the metrics established, you must adapt your strategy based on the specific physical construction of the PCB.

Different high mass designs require different trade-offs. Below are common scenarios encountered at APTPCB.

1. Heavy Copper Power Boards (4 oz+)

- Challenge: Inner layers absorb massive amounts of heat.

- Trade-off: You need a very long soak time.

- Risk: Flux may exhaust (dry out) before reflow if the soak is too long.

- Solution: Use a solder paste with a high-activity flux designed for extended profiles.

2. Metal Core PCBs (MCPCB)

- Challenge: The aluminum or copper backing dissipates heat rapidly.

- Trade-off: Requires high energy input but fast conveyor speed is often impossible.

- Risk: The board acts as a radiator, cooling the solder before it wets.

- Solution: Bottom-side heating is crucial. Ensure the Metal Core PCB is not touching the conveyor rails directly if they act as heat sinks.

3. Ceramic Substrates

- Challenge: Ceramics are brittle and sensitive to thermal shock.

- Trade-off: Reflow and thermal profile for ceramic requires a very slow ramp rate (<1°C/sec).

- Risk: Cracking the substrate or lifting pads.

- Solution: Extend the total profile length significantly. Avoid rapid cooling.

4. Large Backplanes

- Challenge: Massive surface area causes uneven heating (shadowing).

- Trade-off: High air velocity helps transfer heat but can shift light components.

- Risk: High Delta T between the center and edges of the board.

- Solution: Lower the conveyor speed to allow thermal saturation.

5. Mixed Technology (High Mass + Tiny Components)

- Challenge: Soldering a heavy heat sink next to a 0201 resistor.

- Trade-off: The 0201 will overheat before the heat sink is ready.

- Risk: Tombstoning of small parts or burning of plastic connectors.

- Solution: Use vapor phase soldering or selective soldering instead of standard convection reflow if the Delta T is unmanageable.

6. High-Reliability Aerospace

- Challenge: Zero tolerance for voiding.

- Trade-off: Vacuum reflow reduces voids but adds cycle time.

- Risk: Trapped volatiles in thick boards.

- Solution: Optimize the pre-reflow soak to ensure full volatile outgassing.

From design to manufacturing (implementation checkpoints)

After selecting the right strategy for your scenario, you must execute the profiling process systematically.

Follow these checkpoints to implement high mass board thermal profiling on the production line.

- Thermocouple Attachment: Do not use Kapton tape alone. Use high-temperature solder or conductive epoxy to attach thermocouples to the actual solder joints of the heaviest components.

- Oven Capability Check: Verify that your reflow oven has enough heating zones (minimum 8, preferably 10+) to control the soak phase precisely.

- Cleaning and Surface Preparation: Heavy copper oxidizes easily. Proper cleaning and surface preparation are vital. Ensure pads are free of oxides to allow the solder to wet quickly, reducing the thermal demand.

- Soak Zone Adjustment: Set a "flat" soak profile (e.g., holding at 180°C for 90 seconds) to allow the heavy copper planes to reach equilibrium with the surface components.

- Conveyor Speed: Start with a slower speed. High mass boards need "time in zone" to absorb energy.

- Nitrogen Environment: For Heavy Copper PCBs, use Nitrogen (N2) reflow. It improves wetting and widens the process window, allowing for slightly lower peak temperatures.

- Cooling Slope Management: High mass boards hold heat. If cooled too slowly, the solder grain becomes coarse (brittle). If cooled too fast, the board warps. Aim for a controlled cool-down.

- First Article Inspection (FAI): Run a "Golden Board" with thermocouples. Do not rely on simulation alone.

- X-Ray Validation: Use X-Ray Inspection to check for barrel fill on through-hole parts and voiding under large BGAs or QFNs.

- Cross-Sectioning: For critical runs, perform destructive testing (cross-section) to verify the intermetallic compound (IMC) thickness.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a checklist, engineers often fall into traps that compromise the reliability of high mass assemblies.

Avoid these frequent errors when establishing your thermal profile.

- Ramping Too Fast:

- Mistake: Increasing the heat quickly to save time.

- Result: Thermal shock damages ceramic caps; solvent pop causes solder balls.

- Correction: Keep the pre-heat ramp below 2°C/second.

- Measuring Air Instead of Mass:

- Mistake: Placing thermocouples floating in the air or on the PCB edge.

- Result: The profile looks good, but the center of the board is cold.

- Correction: Embed thermocouples into the center ground plane or under the largest BGA.

- Insufficient Soak Time:

- Mistake: Using a standard "tent" profile (linear ramp to peak).

- Result: High Delta T. Small parts reflow, heavy parts result in cold solder.

- Correction: Use a trapezoidal profile with a distinct soak plateau.

- Ignoring Component Specs:

- Mistake: Exceeding the maximum temperature rating of connectors to melt the solder on the heavy board.

- Result: Melted plastic bodies or damaged internal dies.

- Correction: Use heat shields or fixtures to protect sensitive components.

- Neglecting Cool Down:

- Mistake: Letting the heavy board exit the oven hot.

- Result: Solder joints remain liquid while the board moves, causing disturbed joints.

- Correction: Ensure the exit conveyor has sufficient cooling fans or extend the cooling zone.

- Reusing Standard Profiles:

- Mistake: Applying a standard FR4 profile to a Ceramic PCB.

- Result: Substrate fracture due to mismatch in thermal expansion.

- Correction: Build a custom profile from scratch for every high mass NPI.

FAQ

These questions address specific nuances that often arise during the profiling of heavy boards.

1. What is the maximum acceptable Delta T for high mass boards? Ideally, keep it under 10°C. However, for extremely heavy copper boards, up to 15°C is often accepted, provided the coldest joint reaches liquidus and the hottest component stays safe.

2. Why is Nitrogen (N2) recommended for high mass profiling? Nitrogen prevents oxidation during the long soak and reflow times required for these boards. It improves wetting forces, allowing the solder to flow better even if the temperature is marginally lower.

3. How do I profile a board with a thick aluminum core? You must account for the rapid heat loss. Often, these boards require higher zone temperatures than FR4. Ensure the thermocouple is attached firmly to the aluminum base to monitor its temperature lag.

4. Can I use wave soldering for high mass boards? Yes, but pre-heating is critical. The board must enter the wave hot (110°C–130°C topside) to prevent thermal shock and ensure the solder flows up the barrel.

5. How does "reflow and thermal profile for ceramic" differ from FR4? Ceramic has lower thermal expansion but is brittle. The ramp-up and cool-down rates must be much slower to prevent the ceramic from cracking due to thermal stress.

6. What if my flux burns off before reflow? This happens if the soak is too long or hot. Switch to a solder paste with a "high mass" or "anti-slump" flux formulation designed for extended profiles.

7. How many thermocouples should I use? For a high mass NPI, use at least 5 to 7. Place them on: the leading edge, trailing edge, center, heaviest component, lightest component, and the PCB substrate itself.

8. What is the role of "cleaning and surface preparation" in profiling? Dirty pads require more thermal energy to wet. By ensuring pristine surfaces, you reduce the barrier to wetting, making the thermal profile more effective at standard temperatures.

Glossary (key terms)

To communicate effectively with your assembly house, familiarize yourself with these technical terms.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Thermal Mass | The ability of a material (or PCB) to absorb and store heat energy. |

| Soak Zone | The portion of the reflow profile where temperature is held steady to equalize the board. |

| Liquidus | The temperature at which the solder alloy becomes completely liquid (e.g., 217°C for SAC305). |

| Delta T (ΔT) | The maximum temperature difference between any two points on the PCB at a given time. |

| Wetting | The ability of molten solder to spread and bond to the metal pad. |

| Cold Solder Joint | A defect where the solder did not fully melt or wet the pad, often due to insufficient heat. |

| Tombstoning | A defect where a component stands up on one end due to uneven wetting forces. |

| Thermal Shock | Damage caused by a rapid change in temperature (ramp rate too high). |

| Eutectic | An alloy composition that melts at a single, specific temperature. |

| Flux Activation | The temperature range where flux cleans oxides from the metal surfaces. |

| Voiding | Air or gas pockets trapped inside the hardened solder joint. |

| Thermocouple | A sensor used to measure temperature at specific points on the PCB. |

Conclusion (next steps)

High mass board thermal profiling is not just a machine setting; it is an engineering discipline that balances physics, chemistry, and material science. Successfully assembling heavy copper, metal core, or complex multilayer boards requires a departure from standard operating procedures. It demands extended soak times, precise Delta T management, and rigorous validation through X-ray and cross-sectioning.

If you are designing a high-power or high-reliability device, early collaboration with your manufacturer is essential. When requesting a quote or DFM review from APTPCB, please provide:

- Gerber files indicating copper weights (inner and outer layers).

- Stack-up details (core thickness, prepreg types).

- Component datasheet for any large or temperature-sensitive parts.

- Specific test requirements (e.g., IPC Class 3, voiding percentage limits).

By addressing the thermal challenges of high mass designs upfront, you ensure a robust manufacturing process and a reliable final product.