Key Takeaways

- Core Definition: A Shock Logger PCB is a specialized circuit board designed to detect, measure, and record sudden impact events (G-force) over time.

- Critical Metric: The sampling rate must be at least 10 times the frequency of the shock pulse to capture the peak accurately.

- Power Management: Ultra-low sleep current is vital for logistics applications where the device must last months on a coin cell.

- Mechanical Design: Sensor placement is critical; placing accelerometers near mounting holes or board edges can introduce mechanical noise.

- Validation: Drop testing and vibration tables are non-negotiable for validating the durability of the PCB assembly itself.

- Integration: Modern designs often combine shock sensing with a Temperature Logger PCB or Vibration Logger PCB for holistic environmental monitoring.

- Manufacturing: Conformal coating is often required to prevent component detachment or shorting during high-impact events.

What Shock Logger PCB really means (scope & boundaries)

To understand how to build these devices, we must first define the specific engineering boundaries of a Shock Logger PCB.

Unlike a standard data logger that might record slow-changing variables like humidity, a shock logger must capture transient, high-speed events. A shock is a physical stimulus that occurs over a very short duration—often milliseconds or microseconds. Therefore, the PCB design focuses heavily on high-speed analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) and robust mechanical reliability.

At its heart, this PCB integrates a MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) accelerometer or a piezoelectric sensor. The firmware runs in a deep sleep mode, waking up only when a specific G-force threshold is breached. This "trigger-based" architecture distinguishes it from continuous recorders.

For engineers working with APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), the primary challenge is ensuring the PCB itself survives the shock it is measuring. The interconnects, solder joints, and battery contacts must withstand forces that could exceed 100G or even 1000G, depending on the application.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once you understand the definition and scope, the next step is to quantify performance using specific metrics.

Evaluating a Shock Logger PCB requires looking beyond standard electrical specs. You must analyze how the board handles physical physics and data integrity under stress.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical Range / Factors | How to Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Range (G) | Determines the maximum impact the board can record without "clipping" (flatlining at max value). | ±16G (Logistics) to ±2000G (Ballistics). | Use a centrifuge or drop tower to verify linearity up to the max rating. |

| Sampling Rate (Hz) | If the rate is too slow, the logger will miss the true peak of the impact (aliasing). | 1 kHz to 100 kHz. Should be 10x the pulse frequency. | Compare recorded waveform against a calibrated reference oscilloscope. |

| Bandwidth (Hz) | Defines the frequency range the sensor can physically detect before attenuation. | 0 Hz (DC) to 5 kHz. | Frequency sweep test using a vibration shaker. |

| Resolution (Bit Depth) | Higher bits allow detection of smaller changes, crucial for distinguishing noise from data. | 8-bit (Rough) to 24-bit (Precision). | Analyze the noise floor in a static (0G) state. |

| Sleep Current | Critical for shelf life. Loggers spend 99% of their life waiting for a shock. | < 5 µA is the gold standard. | Use a precision source measure unit (SMU) during sleep mode. |

| Wake-up Time | The delay between the trigger event and the first recorded data point. | < 1 ms. If too slow, the initial impact spike is lost. | Trigger the device and measure the latency to the first memory write. |

| Memory Write Speed | High-speed shocks generate data faster than some flash memory can write. | SPI/I2C bus speed dependent. | Buffer fill rate testing during continuous high-frequency shock events. |

Selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

Knowing the metrics allows you to choose the right board architecture for your specific operational scenario.

There is no "one size fits all" Shock Logger PCB. A device tracking a fragile glass shipment has different requirements than a logger inside a pile driver. Below are common scenarios and the necessary design trade-offs.

1. Cold Chain Logistics

- Goal: Monitor goods during shipping.

- Trade-off: Prioritize battery life and cost over high-speed sampling.

- Requirement: Often combined with a Temperature Logger PCB circuit. The PCB must function reliably in condensation and freezing temperatures (-40°C).

- APTPCB Recommendation: Use FR4 with standard Tg, but apply conformal coating to protect against moisture.

2. Automotive Crash Testing

- Goal: Record vehicle structural impact.

- Trade-off: Prioritize sampling rate and G-range over battery life.

- Requirement: High-G sensors (±200G or more). The data must be written to non-volatile memory instantly to prevent loss if power is cut during the crash.

- Design Tip: Use robust connectors (e.g., Molex automotive grade) rather than standard headers.

3. Industrial Equipment Monitoring

- Goal: Predictive maintenance on motors and gears.

- Trade-off: Prioritize bandwidth and resolution.

- Requirement: This is often a Vibration Logger PCB hybrid. It needs to detect subtle shifts in vibration patterns, not just single shocks.

- Design Tip: The sensor must be mechanically coupled rigidly to the mounting hole to transfer vibration accurately.

4. Aerospace and Defense

- Goal: Missile or avionics testing.

- Trade-off: Reliability is the only priority. Cost is secondary.

- Requirement: Extreme G-force survival (up to 20,000G).

- APTPCB Recommendation: Use Polyimide or high-performance laminates. All heavy components must be underfilled or staked with epoxy.

5. Consumer Electronics Drop Testing

- Goal: Testing phone or laptop durability.

- Trade-off: Size constraints.

- Requirement: Miniaturization. The PCB must fit inside the prototype device.

- Design Tip: Use HDI (High Density Interconnect) technology and 0201 components to save space.

6. Railway Cargo Monitoring

- Goal: Long-duration tracking of rail cars.

- Trade-off: Massive storage capacity and solar charging integration.

- Requirement: The PCB needs efficient power harvesting circuits and large flash memory arrays.

- Design Tip: Ensure the PCB layout isolates the sensitive analog sensor from the noisy power harvesting switching regulators.

From design to manufacturing (implementation checkpoints)

After selecting the right approach for your scenario, you must execute the design and manufacturing phases with strict quality controls.

Manufacturing a Shock Logger PCB introduces risks that don't exist for static electronics. If a solder joint is weak, the very event you are trying to record (the shock) will break the recorder.

| Checkpoint | Recommendation | Risk if Ignored | Acceptance Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sensor Layout | Place MEMS sensors near the center of the board or mounting points, away from high-stress edges. | Board warping during shock causes false data or sensor cracking. | Stress simulation (FEA) during design phase. |

| 2. Component Orientation | Align heavy components (inductors, capacitors) parallel to the axis of least bending. | Ceramic capacitors can crack under flex, causing shorts. | Visual inspection and bending tests. |

| 3. Battery Connection | Use through-hole battery holders or spot-welded tabs. Avoid simple spring contacts for high-G. | Momentary power loss during impact resets the MCU. | Shake table test while monitoring power rails. |

| 4. Decoupling Capacitors | Place capacitors as close to the sensor and MCU power pins as possible. | Power ripple during wake-up spikes corrupts ADC readings. | Impedance analysis of the power distribution network (PDN). |

| 5. Solder Alloy | Use SAC305 or specialized high-reliability alloys. Avoid brittle formulations. | Solder joints fracture under repetitive shock. | Shear testing of sample joints. |

| 6. Underfill / Staking | Apply epoxy staking to large components (electrolytic caps, heavy inductors). | Components shear off the pads during impact. | Pull strength test after curing. |

| 7. Conformal Coating | Apply acrylic or silicone coating. | Moisture or conductive debris causes shorts during field use. | UV light inspection (if coating has UV tracer). |

| 8. Test Points | Do not place test points on high-speed signal lines. Use zero-ohm resistors if needed. | Acts as an antenna for noise; degrades signal integrity. | Signal integrity simulation. |

| 9. PCB Material | Use high-Tg FR4 or Polyimide for harsh environments. | Pad cratering or delamination at high temperatures/shocks. | Thermal cycling test (-40°C to +85°C). |

| 10. Trace Routing | Avoid 90-degree angles on high-speed lines; use teardrops on pads. | Stress concentration at corners leads to trace fractures. | Automated Optical Inspection (AOI). |

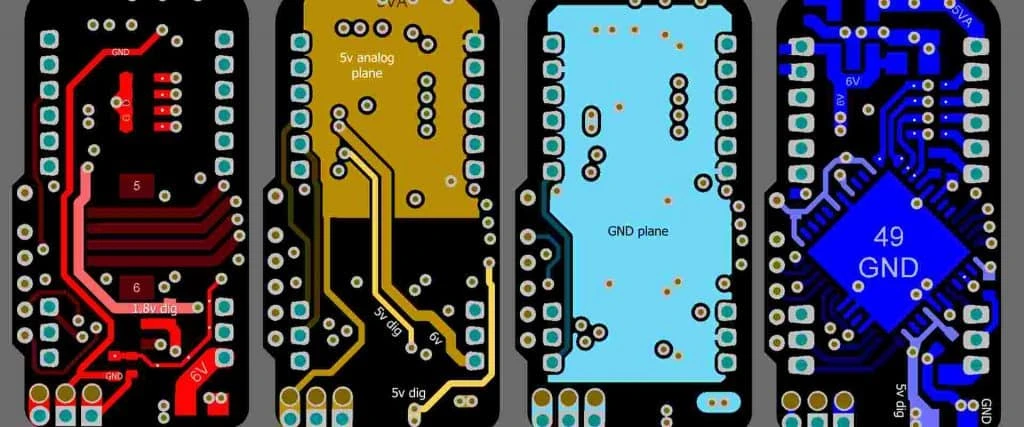

| 11. Grounding | Use a solid ground plane directly under the sensor. | Ground loops introduce noise that mimics shock data. | Noise floor measurement. |

| 12. Data Offload | Include ESD protection on USB or connector pins. | Static discharge from handling destroys the interface. | ESD gun testing. |

For assistance with material selection or stack-up planning, refer to our specialized materials guide.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a solid plan and checklist, specific engineering errors can derail a Shock Logger project.

We have seen many designs fail at APTPCB not because of bad manufacturing, but because of fundamental design oversights regarding shock physics.

1. Confusing Shock with Vibration

- Mistake: Using a vibration sensor (high sensitivity, low range) to measure shock (low sensitivity, high range).

- Result: The sensor saturates (clips) instantly upon impact, providing no useful data.

- Correction: Select a sensor specifically rated for the expected G-force (e.g., 50G for shipping, 200G for drops).

2. Ignoring Mechanical Resonance

- Mistake: The PCB's natural frequency matches the shock frequency.

- Result: The board acts like a tuning fork, amplifying the shock and destroying components.

- Correction: Calculate the resonant frequency of the PCB assembly. Add mounting points to shift the resonance higher than the measurement bandwidth.

3. Poor Battery Management

- Mistake: Assuming the battery voltage stays constant during a shock.

- Result: Batteries, especially coin cells, have internal resistance that increases with age. A wake-up current spike drops the voltage, resetting the logger.

- Correction: Add a large tantalum or ceramic bulk capacitor parallel to the battery to handle the wake-up surge.

4. Aliasing the Signal

- Mistake: Sampling at exactly the Nyquist rate (2x frequency).

- Result: You capture the frequency but miss the amplitude peak, underestimating the shock severity.

- Correction: Oversample by at least 10x. If the shock pulse is 10ms (100Hz), sample at 1kHz or higher.

5. Neglecting Data Retention

- Mistake: Buffering data in RAM before writing to Flash.

- Result: If the shock disconnects the battery, the data in RAM is lost forever.

- Correction: Use FRAM (Ferroelectric RAM) or ensure the power supply capacitance can hold the rail up long enough to flush the buffer to non-volatile memory.

6. Over-constraining the PCB

- Mistake: Screwing the PCB down too tightly without washers or stress relief.

- Result: The PCB cracks around the mounting holes during thermal expansion or shock.

- Correction: Use nylon washers or leave slight tolerance in the mounting holes.

FAQ

Beyond these common errors, engineers often have specific questions regarding the capabilities and limits of Shock Logger PCBs.

Q: What is the difference between a Shock Logger PCB and a Vibration Logger PCB? A: A shock logger triggers on a single, high-amplitude event (impact). A Vibration Logger PCB records continuous, lower-amplitude oscillations over time to analyze frequency spectrums.

Q: Can a Shock Logger PCB also measure temperature? A: Yes, most modern MEMS accelerometers have built-in temperature sensors. Alternatively, a dedicated Temperature Logger PCB circuit can be added to the same board for higher accuracy.

Q: How do I retrieve data from the PCB? A: Common methods include USB (direct connection), Bluetooth Low Energy (wireless), or removing an SD card. For sealed units, NFC or WiFi is often used.

Q: What is the maximum G-force a PCB can withstand? A: Standard FR4 PCBs can withstand 500G-1000G if properly designed. For ballistics (10,000G+), the components usually fail before the PCB, requiring specialized potting (encapsulation).

Q: Does the PCB thickness matter? A: Yes. Thinner PCBs (0.8mm) flex more, which can dampen shock but risks cracking components. Thicker PCBs (1.6mm or 2.0mm) are more rigid, transferring the shock more directly to the sensor.

Q: How long can the battery last? A: It depends entirely on the "sleep current." A well-designed logger with <5µA sleep current can last 1-2 years on a CR2032 coin cell.

Q: Do I need impedance control for a shock logger? A: Generally, no, unless you are using high-speed USB for data offload or high-frequency wireless antennas. You can check requirements using an impedance calculator.

Q: What file formats are used for the data? A: CSV is common for simple loggers. High-end loggers use binary formats to save memory space and battery power during writing.

Q: Can I use a flexible PCB for this? A: Yes, rigid-flex PCBs are excellent for shock loggers as they can fit into tight, irregular spaces within a product housing.

Q: How do I validate the design before mass production? A: You must perform DFM (Design for Manufacturing) checks and build a prototype batch for drop testing.

Related pages & tools

For more depth, explore these resources to assist in your design and manufacturing process.

- Manufacturing Capabilities: Review our full range of PCB manufacturing services to see if we fit your project needs.

- Design Guidelines: Ensure your board is manufacturable by checking our DFM guidelines.

- Material Options: Choose the right substrate for high-impact environments from our materials library.

Glossary (key terms)

To fully utilize these tools and communicate effectively with your manufacturer, you must understand the specific terminology used in shock logging.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Accelerometer | The sensor component (usually MEMS or Piezo) that converts physical acceleration into an electrical signal. |

| ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) | The circuit that converts the continuous voltage from the sensor into digital numbers for the processor. |

| Aliasing | A distortion error where a high-frequency signal is indistinguishable from a lower-frequency one due to low sampling rates. |

| Bandwidth | The range of frequencies the logger can accurately record. |

| Clipping | When the input shock exceeds the sensor's maximum range, resulting in a flat-lined data plot. |

| G-Force | A unit of force equal to the force exerted by gravity. 1G = 9.8 m/s². |

| Hysteresis | The dependence of the sensor's output on its history; a lag between input and output. |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems. Miniature mechanical structures etched into silicon, used for most modern sensors. |

| Nyquist Rate | The minimum sampling rate required to avoid aliasing (must be at least 2x the highest frequency component). |

| Piezoelectric | A material that generates an electric charge when mechanically stressed. Good for high-frequency shock. |

| Sampling Rate | The number of times per second the logger records a data point (measured in Hz or SPS). |

| Sleep Mode | A low-power state where the processor is inactive but the sensor is waiting for a trigger threshold. |

| Trigger Threshold | The specific G-force level that wakes the logger from sleep to begin recording. |

| Conformal Coating | A protective chemical layer applied to the PCB to resist moisture, dust, and chemical contaminants. |

Conclusion (next steps)

With terms defined and the manufacturing process outlined, the path to a reliable Shock Logger PCB is clear.

Success lies in balancing the trade-offs: sampling rate vs. battery life, rigidity vs. flexibility, and sensitivity vs. durability. Whether you are building a device for cold chain logistics or aerospace testing, the PCB is the foundation of your data integrity.

APTPCB specializes in high-reliability PCB fabrication and assembly. When you are ready to move from concept to production, ensure you have the following ready for a quote:

- Gerber Files: The standard design files.

- BOM (Bill of Materials): Specifically highlighting the sensor and battery holder part numbers.

- Stack-up Requirements: If you need specific rigid or flex materials.

- Test Specifications: Define the G-force limits the board must survive.

Contact us today to review your design and ensure your shock logger performs when it matters most.