A Shock Sensor PCB is a specialized circuit board assembly designed to detect sudden mechanical impacts, vibrations, or physical trauma. Unlike continuous vibration monitors, these boards are engineered to trigger a specific response—such as an alarm, a system shutdown, or a data log—when a G-force threshold is exceeded. Whether used in automotive airbag ECUs, industrial machinery safety stops, or residential glass-break detectors, the reliability of the PCB layout and assembly is just as critical as the sensor component itself.

At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we frequently encounter designs where poor mechanical coupling or improper grounding renders a high-quality shock sensor useless. This guide provides the engineering rules, specifications, and troubleshooting workflows necessary to manufacture reliable Shock Sensor PCBs.

Shock Sensor PCB quick answer (30 seconds)

If you are designing or sourcing a Shock Sensor PCB, adhere to these fundamental principles to ensure accurate detection and prevent false positives:

- Mechanical Coupling is Critical: The sensor must be placed on a rigid section of the PCB, ideally within 10mm of a mounting hole, to ensure shock energy is transferred efficiently from the enclosure to the sensor.

- Stiff Substrate Required: Use High-Tg FR4 or Metal Core PCBs to minimize board flex, which can dampen high-frequency shock waves before they reach the sensor.

- Zero-Damping Assembly: Do not use conformal coating or potting compounds directly over mechanical sensing elements (like spring coils or piezo diaphragms) unless the manufacturer explicitly permits it, as this alters sensitivity.

- Filter Power Supply Noise: Piezoelectric shock sensors are high-impedance devices; power supply ripple can look exactly like a shock signal. Use local decoupling capacitors close to the amplifier stage.

- Orientation Matters: Most shock sensors have a sensitive axis (X, Y, or Z). Align the PCB mounting orientation to match the expected direction of impact.

- Validation Method: Define a "Drop Test" or "Impact Hammer" standard in your manufacturing files, not just an electrical continuity test.

When Shock Sensor PCB applies (and when it doesn’t)

Shock sensors are distinct from other motion detection technologies. Knowing when to use a dedicated Shock Sensor PCB versus alternative sensor types is the first step in system architecture.

Use a Shock Sensor PCB when:

- Impact Detection is required: You need to detect a single, high-force event (e.g., a package being dropped, a car crash, or a window being struck).

- Tamper Protection is needed: You are designing a security enclosure that must trigger an alarm if someone attempts to drill or hammer into it.

- Wake-up on Shake: You need a low-power device to wake up from sleep mode only when physically disturbed.

- Machine Protection: You need to instantly cut power to a spindle or motor if a collision occurs.

Do NOT use a Shock Sensor PCB when:

- You need to detect gradual orientation changes: A Tilt Sensor PCB is better suited for detecting if an object has tipped over or changed angle slowly.

- You need to detect human presence without contact: A PIR Sensor PCB (Passive Infrared) or Microwave Sensor PCB is required for detecting motion via heat or Doppler shift, as shock sensors require physical energy transfer.

- You need to monitor perimeter breaches without impact: A Barrier Sensor PCB (infrared beam) or Door Sensor PCB (magnetic reed switch) is standard for detecting open/close states where no impact force is generated.

- You need precise vibration analysis: If you need to measure the frequency spectrum of a motor (FFT analysis), a wide-bandwidth MEMS accelerometer is superior to a simple threshold-based shock sensor.

Shock Sensor PCB rules and specifications (key parameters and limits)

The following table outlines the critical design parameters for a functional Shock Sensor PCB. Ignoring these rules often leads to "deaf" sensors or systems that trigger falsely due to ambient noise.

| Rule / Parameter | Recommended Value / Range | Why it matters | How to verify | If ignored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB Thickness | $\ge$ 1.6mm (Standard) | Thinner boards flex, acting as a shock absorber and dampening the signal. | Caliper measurement. | Reduced sensitivity; sensor fails to detect light impacts. |

| Sensor Placement | < 10mm from mounting screw | Maximizes mechanical coupling between the chassis and the PCB. | CAD Layout Review. | Signal attenuation; impact energy dissipates in the FR4. |

| Trace Width (Signal) | Minimum (e.g., 6-8 mil) | Reduces parasitic capacitance on high-impedance piezo lines. | Impedance calculation. | Increased noise floor; higher risk of false alarms. |

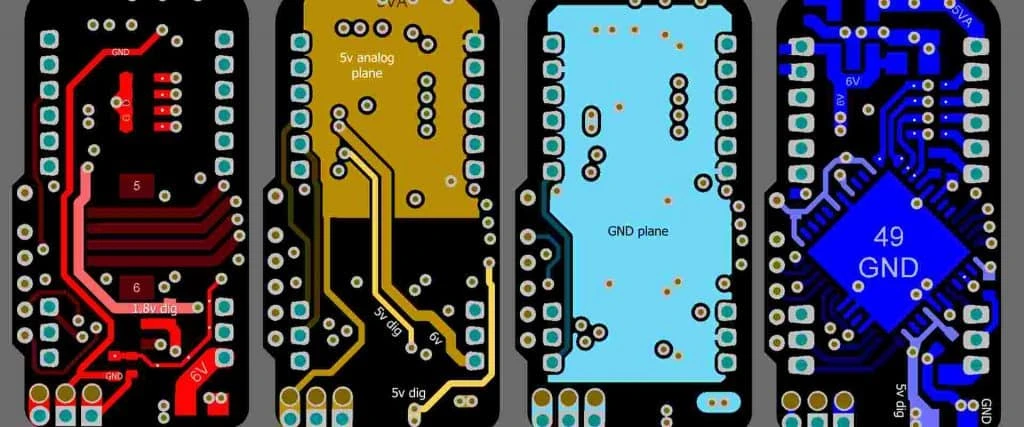

| Grounding Strategy | Star Ground / Solid Plane | Prevents ground loops from inducing voltage spikes that mimic shock signals. | Gerber Viewer check. | False triggers from EMI or nearby relay switching. |

| Solder Alloy | SAC305 or SnPb (if exempt) | Shock sensors undergo high mechanical stress; brittle joints will fracture. | Shear testing / Cross-section. | Intermittent failures after the first few impacts. |

| Resonant Frequency | Match Sensor to Application | The PCB's natural frequency should not cancel out the sensor's target frequency. | Modal analysis (simulation). | "Blind spots" where specific impact frequencies are ignored. |

| Conformal Coating | Mask Sensor Area | Coating adds mass and damping to mechanical sensor elements. | Visual Inspection (UV light). | Sensor sensitivity drifts or becomes unpredictable. |

| Mounting Torque | Specific to screw size (e.g., 0.6 Nm) | Loose boards rattle (false noise); overtightened boards warp (stress). | Torque screwdriver. | Inconsistent readings across different production batches. |

| Debounce Time | 10ms - 500ms (Software/RC) | Mechanical contacts bounce; raw signals need conditioning. | Oscilloscope capture. | Multiple triggers for a single impact event. |

| Operating Temp | -40°C to +85°C (Industrial) | Piezo materials and mechanical springs change properties with heat. | Thermal cycling test. | Sensitivity changes drastically in winter vs. summer. |

Shock Sensor PCB implementation steps (process checkpoints)

Implementing a shock sensor requires a tight integration between the mechanical enclosure design and the PCB layout. Follow these steps to ensure success.

1. Define the Impact Profile Determine the G-force range (e.g., 2G for handling, 50G for crash) and the frequency of the shock. This dictates whether you use a simple spring switch, a piezo film, or a MEMS accelerometer.

2. Select the Substrate Material For most security and industrial applications, standard FR4 is sufficient, provided it is thick enough (1.6mm or 2.0mm). For high-temperature or high-rigidity requirements, consider a Rigid PCB with a higher Tg to maintain stiffness over time.

3. Component Placement & Orientation Place the sensor at the "stiffest" point of the board—usually near a corner or a mounting post. Align the sensor's sensitive axis with the expected direction of impact. If the device can be dropped from any angle, consider using three orthogonal sensors or a 3-axis MEMS device.

4. Routing and Noise Immunity Route the analog output of the sensor as a differential pair if possible, or surround it with a ground guard ring. Keep these traces away from high-current switching regulators or relay coils.

5. Assembly and Soldering During assembly, ensure the reflow profile does not exceed the sensor's thermal limits. Some mechanical shock sensors are sensitive to heat and may require hand soldering or selective soldering after the main reflow process.

6. Mechanical Integration When mounting the PCB into the enclosure, use metal standoffs or rigid plastic pillars. Avoid rubber grommets or soft foam tape for the PCB mounting, as these isolate the PCB from the very shock waves you are trying to detect.

7. Calibration and Testing Every Shock Sensor PCB must be calibrated. This often involves a "tap test" or a controlled drop test during the Final Quality Control (FQC) stage to verify the threshold settings.

Shock Sensor PCB troubleshooting (failure modes and fixes)

When a Shock Sensor PCB fails, it usually fails in one of two ways: it triggers constantly (false positive) or never triggers (false negative).

Symptom: False Alarms (Triggering without impact)

- Cause 1: Power Supply Noise. Ripple from a DC-DC converter is coupling into the high-impedance sensor input.

- Fix: Add a low-pass RC filter at the sensor input and improve decoupling capacitors.

- Cause 2: Acoustic Resonance. The PCB or enclosure is vibrating from ambient sound (e.g., loud machinery or speakers).

- Fix: Adjust the mechanical mounting to shift the resonant frequency or add software filtering to ignore continuous vibration.

- Cause 3: Loose Mounting. The PCB is rattling against the enclosure.

- Fix: Verify screw torque and ensure standoffs are flush.

Symptom: No Response to Impact (Low Sensitivity)

- Cause 1: Mechanical Damping. The PCB is mounted on rubber washers or the enclosure is too soft (plastic absorbs shock).

- Fix: Remove damping materials; mount PCB directly to the chassis; move sensor closer to mounting points.

- Cause 2: Incorrect Orientation. The impact is coming from the Z-axis, but the sensor is a unidirectional X-axis sensor.

- Fix: Re-orient the sensor or switch to an omnidirectional component.

- Cause 3: Signal Saturation. The amplifier gain is too high, causing the signal to rail immediately, or too low to register.

- Fix: Adjust the gain resistor values in the op-amp circuit.

Symptom: Intermittent Operation

- Cause: Solder Joint Fracture. The shock of the impact has cracked the solder joints of the sensor itself.

- Fix: Use a larger solder pad layout (footprint) for mechanical strength; consider underfill or adhesive staking for heavy sensors.

How to choose Shock Sensor PCB (design decisions and trade-offs)

Choosing the right architecture for your Shock Sensor PCB depends on cost, precision, and power consumption.

1. Piezoelectric vs. MEMS vs. Mechanical Spring

- Mechanical Spring/Ball: Lowest cost, zero power consumption (passive). Best for simple "wake-up" features or gross movement detection. Downside: Prone to contact bounce and oxidation; low precision.

- Piezoelectric Elements: High sensitivity, passive (generates voltage), excellent for high-frequency impact (glass break). Downside: High impedance output requires careful shielding; brittle ceramic material.

- MEMS Accelerometers: High precision, digital output, programmable thresholds. Best for quantitative analysis and complex triggers. Downside: Requires active power; higher BOM cost; requires microcontroller firmware.

2. Security vs. Industrial Applications

- Security Systems: Often combine multiple sensor types. A Shock Sensor PCB detects forced entry (hammering), while a Door Sensor PCB detects opening, and a PIR Sensor PCB detects movement inside. Integrating these onto one main control board reduces wiring but increases board complexity.

- Industrial Monitoring: Focuses on predictive maintenance. Here, the "shock" is often a catastrophic failure. These boards require robust Security Equipment PCB standards, including high-voltage isolation and surge protection.

3. Standalone vs. Integrated

- Standalone Module: A small PCB containing just the sensor and a connector. Easier to replace and mount in optimal locations.

- Integrated Mainboard: The sensor is on the main control PCB. Lower cost, but limits placement options (the mainboard might not be in the best spot to detect impact).

Shock Sensor PCB FAQ (cost, lead time, common defects, acceptance criteria, Design for Manufacturability (DFM) files)

Q: How much does a Shock Sensor PCB cost to manufacture? A: The PCB itself is standard cost (rigid FR4). However, the assembly cost can be higher due to the need for specialized testing (drop testing) and potentially non-standard component placement (hand-soldering sensitive mechanical switches).

Q: What is the lead time for Shock Sensor PCB prototypes? A: Standard lead time is 24-48 hours for the bare PCB. If you require full turnkey assembly including sourcing specific MEMS sensors or piezo elements, allow 1-2 weeks for component procurement.

Q: Can I use a Flex PCB for a shock sensor? A: Generally, no. Flex PCBs absorb energy. However, you can use a rigid-flex design where the sensor is on the rigid section and the flex cable connects it to the main unit. This isolates the sensor from cable strain.

Q: How do I specify acceptance criteria for shock sensors? A: You must define a functional test. For example: "Unit must trigger output pin high when dropped from 10cm height onto a wooden surface." Visual inspection alone is insufficient for mechanical sensors.

Q: What files does APTPCB need for DFM? A: We need Gerber files, the BOM (Bill of Materials), and specifically the datasheet of the shock sensor component. We check the footprint to ensure the pads are large enough for mechanical stability.

Q: Why is my shock sensor triggering when the relay turns on? A: This is EMI (Electromagnetic Interference). The sudden current draw of the relay creates a magnetic field or ground bounce that induces a voltage in the high-impedance sensor traces. Improve your ground plane separation.

Q: How does this differ from a Tilt Sensor PCB? A: A Tilt Sensor PCB uses gravity to detect angle (static or slow change). A Shock Sensor PCB uses inertia to detect rapid acceleration (impact). Some MEMS sensors can do both, but dedicated mechanical sensors are usually one or the other.

Resources for Shock Sensor PCB (related pages and tools)

- Security Equipment PCB: Explore manufacturing standards for alarm and intrusion detection systems.

- Rigid PCB Manufacturing: Specifications for the standard FR4 substrates used in most shock sensor applications.

- PCBA Testing & Quality: Learn about the testing protocols APTPCB uses to verify sensor functionality.

- SMT & THT Assembly: Capabilities for assembling mixed-technology boards often found in industrial sensor nodes.

Shock Sensor PCB glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| G-Force | A unit of force equal to the force exerted by gravity. Shock sensors are rated by the G-force required to trigger them. |

| Piezoelectric Effect | The ability of certain materials (ceramics, crystals) to generate an electric charge in response to applied mechanical stress. |

| Hysteresis | The difference between the threshold at which the sensor triggers and the threshold at which it resets. Prevents rapid on/off oscillation. |

| Sensitivity Axis | The specific direction (X, Y, or Z) in which the sensor is most capable of detecting impact. |

| Debounce | A method (hardware or software) used to filter out the "ripple" or multiple transitions caused by mechanical contact vibration. |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems. Miniature sensors etched into silicon that can measure acceleration and shock with high precision. |

| Omnidirectional | A sensor capable of detecting impacts from any direction, regardless of orientation. |

| Parasitic Capacitance | Unwanted capacitance between PCB traces that can filter out high-frequency shock signals or couple noise into the circuit. |

| Resonant Frequency | The natural frequency at which an object vibrates. If the PCB resonance matches the noise source, false alarms occur. |

| Latch Mode | A sensor configuration where the output stays active after a shock until manually reset, as opposed to momentary output. |

Request a quote for Shock Sensor PCB (Design for Manufacturability (DFM) review + pricing)

Ready to move your design from prototype to production? APTPCB provides comprehensive DFM reviews to ensure your Shock Sensor PCB is optimized for mechanical stability and signal integrity.

What to send for an accurate quote:

- Gerber Files: RS-274X format preferred.

- BOM: Include part numbers for the specific sensor (Piezo/MEMS/Spring).

- Assembly Drawing: Highlight any special mounting requirements or "keep-out" zones for conformal coating.

- Test Requirements: Specify if you need functional drop testing or impact verification during QC.

Conclusion (next steps)

Designing a reliable Shock Sensor PCB requires more than just connecting a sensor to a microcontroller; it demands a holistic approach to mechanical coupling, substrate rigidity, and noise immunity. Whether you are building a simple glass-break detector or a complex automotive crash sensor, the layout and assembly quality determine the success of the device. By following the rules of rigid mounting, proper grounding, and rigorous testing, you can eliminate false alarms and ensure your system reacts only when it truly matters.