Sulfur dioxide (SO2) detection requires high-precision electronics capable of measuring nano-ampere currents without interference. An SO2 Sensor PCB acts as the critical interface between the chemical sensing element and the digital processing unit, requiring strict adherence to signal integrity and material stability rules. Engineers must manage leakage currents, thermal noise, and environmental corrosion to ensure accurate readings in industrial safety or environmental monitoring applications.

Quick Answer (30 seconds)

Designing a reliable SO2 Sensor PCB requires prioritizing low-noise signal paths and chemical resistance.

- Surface Finish: Use ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) to ensure a flat surface for sensor seating and prevent oxidation in corrosive environments.

- Leakage Control: Implement guard rings around high-impedance sensor inputs (Working Electrode) to shunt leakage currents away from the measurement path.

- Material Selection: Standard FR4 is sufficient for most industrial units, but high-impedance areas may require PTFE or specialized cleaning processes to remove flux residues.

- Isolation: Physically separate the analog sensor front-end from digital switching regulators and communication lines (like RS485 or Wi-Fi).

- Thermal Stability: Place temperature sensors immediately next to the gas sensor to compensate for the temperature coefficient of the electrochemical cell.

- Validation: Verify zero-point stability and span accuracy using calibrated gas mixtures before final potting or enclosure sealing.

When Sulfur dioxide (SO2) Sensor PCB applies (and when it doesn’t)

Understanding the specific operational environment helps determine if a specialized SO2 Sensor PCB design is necessary or if a generic controller is sufficient.

When to use a dedicated SO2 Sensor PCB:

- Industrial Safety Monitoring: When detecting toxic leaks in petrochemical plants or mining operations where SO2 levels can be fatal.

- Emission Control Systems: For flue gas desulfurization (FGD) scrubbers requiring continuous feedback loops.

- Environmental Air Quality Stations: When measuring low-concentration (ppb level) SO2 for regulatory compliance.

- Portable Gas Detectors: Handheld units requiring compact layouts with minimal power consumption and high vibration resistance.

- Multi-Gas Instruments: Devices integrating SO2 detection alongside an Ammonia Sensor PCB or Chlorine Sensor PCB, requiring complex signal routing.

When it typically does not apply:

- General Indoor Air Quality (IAQ): Standard IAQ monitors usually focus on CO2 or VOCs; SO2 is rarely a primary concern in residential settings.

- High-Temperature Combustion Chambers: The PCB itself cannot survive inside a furnace; remote sensing with a probe is required, keeping the PCB in a cooler zone.

- Simple Smoke Detection: Optical smoke detectors do not require the electrochemical interface circuitry used for specific gas sensing.

- Non-Critical Educational Kits: Basic hobbyist modules often skip the necessary guard rings and reference voltage stability required for industrial accuracy.

Rules & specifications

To ensure the SO2 Sensor PCB functions correctly under harsh conditions, specific design rules must be followed.

| Rule | Recommended Value/Range | Why it matters | How to verify | If ignored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trace Width (Analog) | 0.15 mm - 0.25 mm | Minimizes capacitance on high-impedance lines; reduces pickup area. | Gerber viewer inspection. | Increased noise floor; slower sensor response time. |

| Clearance (HV/Analog) | > 0.5 mm (or per voltage) | Prevents leakage currents from power rails affecting sensor readings. | DRC (Design Rule Check) in CAD. | False positive readings due to leakage current. |

| Surface Finish | ENIG (Immersion Gold) | Provides a flat, oxidation-resistant surface for sensor pads. | Visual inspection; XRF analysis. | Poor contact resistance; signal drift over time. |

| Solder Mask | High-quality LPI (Green/Blue) | Protects traces from sulfur corrosion; defines pad boundaries. | IPC-SM-840 compliance check. | Copper corrosion; potential shorts in humid air. |

| Guard Ring | Surrounding Input Pins | Intercepts surface leakage currents before they reach the sensor input. | Layout review; schematic check. | Unstable zero-point; drift in humid conditions. |

| Via Tenting | Fully Tented (Analog Area) | Prevents flux entrapment and corrosion points near sensitive nodes. | Fabrication drawing notes. | Long-term corrosion; unpredictable leakage paths. |

| Material Tg | > 150°C (High Tg FR4) | Ensures dimensional stability in industrial environments. | Material datasheet review. | PCB warping; solder joint stress fractures. |

| Copper Weight | 1 oz (35 µm) | Standard balance for current handling and etch precision. | Cross-section analysis. | 2 oz may limit fine pitch; 0.5 oz may be fragile. |

| Decoupling Caps | 0.1µF + 10µF (Low ESR) | Stabilizes the reference voltage for the potentiostat circuit. | BOM review; impedance analysis. | Noisy sensor baseline; oscillation in op-amps. |

| Ground Plane | Split (Analog/Digital) | Prevents digital switching noise from coupling into the sensor signal. | Layout visual check. | High noise floor; erratic readings during comms. |

| Conformal Coating | Acrylic or Silicone | Protects the PCB from the corrosive SO2 gas it is measuring. | UV inspection (if tracer used). | Rapid corrosion of components; device failure. |

| Op-Amp Bias Current | < 1 pA (CMOS/JFET) | The sensor output is often nano-amps; high bias current consumes the signal. | Component datasheet check. | Significant measurement error; loss of sensitivity. |

Implementation steps

Moving from specifications to a physical board requires a structured workflow to integrate the sensor correctly.

1. Sensor Technology Selection Identify whether the application requires an electrochemical sensor (standard for toxic gases), a metal oxide sensor (low cost, lower accuracy), or an optical sensor. For high-precision SO2 detection, electrochemical cells are the industry standard. Obtain the datasheet to determine the pin configuration (2-pin, 3-pin, or 4-pin) and the required bias voltage.

2. Schematic Design: The Potentiostat Design the potentiostat circuit. For a 3-electrode sensor (Working, Reference, Counter), the circuit must maintain a fixed potential between the Reference and Working electrodes while driving current through the Counter electrode. Use low-noise, low-input-bias operational amplifiers. Ensure the transimpedance amplifier (TIA) gain resistor is selected to match the sensor's sensitivity (nA/ppm).

3. Component Placement Strategy Place the gas sensor and the analog front-end components (op-amps, reference voltage sources) as close together as possible. This minimizes the length of the high-impedance traces, reducing susceptibility to RF interference. Keep power regulators and microcontrollers at the opposite end of the board.

4. Guard Ring Implementation Route a guard ring around the Working Electrode (WE) trace and the input pin of the TIA op-amp. Connect this guard ring to the same potential as the Working Electrode (usually virtual ground or a specific bias voltage). This ensures that the potential difference across the surrounding dielectric is zero, effectively eliminating surface leakage current.

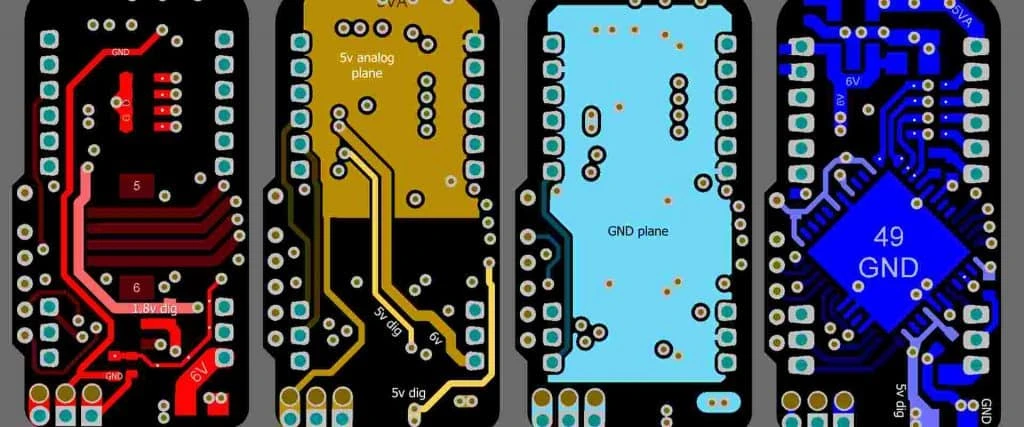

5. Grounding and Power Planes Create separate ground planes for Analog (AGND) and Digital (DGND). Connect them at a single "star point" near the power supply input. This prevents return currents from digital pulses (like LEDs blinking or relays switching) from creating voltage offsets in the sensitive analog ground reference.

6. Thermal Management Design SO2 sensors are temperature sensitive. Place a thermistor or digital temperature sensor immediately adjacent to the gas sensor socket. Do not place heat-generating components (like linear regulators or power MOSFETs) near the sensor, as thermal gradients will cause measurement drift.

7. Layout Verification and DFM Run a Design for Manufacturing (DFM) check. Ensure that the footprint for the sensor socket matches the mechanical pins exactly. Verify that the solder mask expansion is sufficient. At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we recommend checking minimum trace widths against the copper weight to prevent over-etching.

8. Prototyping and Assembly Order the bare PCB and assemble the prototype. During assembly, ensure that no-clean flux is used, or if water-soluble flux is used, the board is washed thoroughly. Flux residue is conductive and will destroy the accuracy of the high-impedance sensor circuit.

9. Calibration and Burn-in Once assembled, the sensor needs a "burn-in" period (often 24-48 hours) to stabilize the electrolyte. After stabilization, perform a zero-calibration using pure nitrogen or zero-air, followed by a span calibration using a known concentration of SO2 gas.

10. Environmental Protection Apply conformal coating to the PCB, strictly masking the gas sensor inlet and the sensor socket contacts. The coating protects the copper traces from the sulfuric acid that can form when SO2 mixes with atmospheric moisture.

Failure modes & troubleshooting

Even with a robust design, issues can arise during testing or field operation.

1. Symptom: Constant High Zero Reading

- Cause: Leakage current on the PCB surface or flux contamination.

- Check: Inspect the area around the TIA input for flux residue. Measure the resistance between the guard ring and the input trace.

- Fix: Clean the PCB with isopropyl alcohol and deionized water. Bake the board to remove moisture.

- Prevention: Use guard rings and strict cleaning protocols during assembly.

2. Symptom: Slow Response to Gas

- Cause: Clogged sensor filter or excessive capacitance on the signal line.

- Check: Inspect the sensor membrane. Check the capacitor values in the feedback loop of the TIA.

- Fix: Replace the sensor filter. Reduce the feedback capacitor value if the bandwidth is too low.

- Prevention: Optimize the RC time constant in the schematic phase.

3. Symptom: Signal Drift with Temperature

- Cause: Mismatch between the sensor's temperature coefficient and the compensation algorithm.

- Check: Log temperature vs. sensor output in a zero-air chamber.

- Fix: Adjust the temperature compensation lookup table in the firmware.

- Prevention: Ensure the temperature sensor is thermally coupled to the gas sensor.

4. Symptom: Erratic/Noisy Readings

- Cause: Power supply ripple or electromagnetic interference (EMI).

- Check: Use an oscilloscope to check the power rails. Look for 50/60Hz hum or switching noise.

- Fix: Add ferrite beads and bypass capacitors to the power input. Shield the sensor assembly.

- Prevention: Use a dedicated low-noise LDO for the analog section.

5. Symptom: Sensor Saturation (Rail Output)

- Cause: Wrong gain resistor value or short circuit.

- Check: Verify the TIA gain resistor matches the sensor's max current output. Check for solder bridges.

- Fix: Swap the gain resistor for a lower value. Remove solder bridges.

- Prevention: Calculate the maximum expected current based on the highest target gas concentration.

6. Symptom: Rapid Corrosion of Traces

- Cause: Exposure to high concentrations of SO2 without protection.

- Check: Visual inspection of black or green corrosion on copper traces.

- Fix: The board is likely destroyed; replace it.

- Prevention: Apply a high-quality conformal coating and use ENIG finish.

7. Symptom: Cross-Sensitivity False Alarms

- Cause: Presence of interfering gases (e.g., CO or NO2) that the sensor also detects.

- Check: Review sensor datasheet for cross-sensitivity factors.

- Fix: Use a selective filter on the sensor or use software algorithms to subtract known interferences if multiple sensors are present.

- Prevention: Select a sensor specifically filtered for SO2.

8. Symptom: Negative Readings

- Cause: Bias voltage polarity incorrect or extreme temperature shift.

- Check: Verify the bias voltage applied to the Counter/Reference electrodes.

- Fix: Correct the bias voltage setting in the potentiostat circuit.

- Prevention: Double-check pinout and bias requirements during schematic capture.

Design decisions

When engineering an SO2 Sensor PCB, several trade-offs must be managed to balance cost, performance, and longevity.

Electrochemical vs. Metal Oxide (MOX) Electrochemical sensors offer linear output and low power consumption, making them ideal for battery-powered portable units. However, they have a limited lifespan (2-3 years). MOX sensors are longer-lasting and cheaper but consume significantly more power (for the heater) and have non-linear outputs. For precision safety equipment, the electrochemical approach is almost always preferred, necessitating the complex TIA circuits discussed above.

Analog vs. Digital Output Sensors Modern sensors sometimes come as modules with built-in I2C or UART output. Using a digital module simplifies the PCB design significantly, as the sensitive analog routing is handled inside the module. However, raw analog sensors allow the engineer to fine-tune the filtering and gain stages for specific applications. If designing a custom Benzene Sensor PCB or CO Sensor PCB alongside SO2, using raw analog sensors often allows for a more integrated and compact multi-gas design.

Material Selection: FR4 vs. PTFE For standard ppm-level detection, high-quality FR4 is sufficient. However, for ppb-level detection (environmental monitoring), the dielectric absorption of FR4 can be a limiting factor. In these extreme cases, using Teflon (PTFE) PCB materials reduces leakage and improves settling time, though at a higher manufacturing cost.

Connector vs. Direct Solder Directly soldering sensors is generally discouraged because the heat can damage the internal electrolyte or wire bonds. Using sockets allows for easy sensor replacement without desoldering. The PCB footprint must be designed to accommodate the specific socket pins, which are often non-standard.

FAQ

1. Can I use the same PCB design for SO2 and other gas sensors? Yes, often. Many electrochemical sensors (like those for CO or H2S) share the standard "4-series" or "7-series" form factor and pinout. However, you must adjust the gain resistor and bias voltage. An Ammonia Sensor PCB might require a different bias polarity compared to an SO2 sensor.

2. What is the typical lifespan of an SO2 Sensor PCB? The PCB itself can last 10+ years if properly coated. The electrochemical sensor plugged into it typically lasts 2-3 years. The design should facilitate easy sensor replacement.

3. How do I handle the "Bias" pin on 4-pin sensors? Some high-performance sensors have a 4th auxiliary electrode to compensate for baseline drift. Your PCB must have a second TIA channel to read this auxiliary signal and subtract it from the main working electrode signal in the firmware.

4. Why is my SO2 reading drifting downwards? This is often due to electrolyte drying out in the sensor or "span drift." It can also be caused by the reference voltage on the PCB drifting. Ensure your voltage reference component has a low temperature coefficient.

5. Is impedance control necessary for SO2 sensor traces? Strict characteristic impedance (like 50 ohms) is not required because the signals are DC or very low frequency. However, "high impedance" layout techniques (guarding, short traces) are critical to prevent noise pickup.

6. Can I wash the PCB after soldering the sensor socket? Yes, and you should. Thorough washing removes flux residues that cause leakage. However, never wash the board with the actual gas sensor installed, as solvents will destroy the sensor.

7. What is the lead time for manufacturing SO2 Sensor PCBs? Standard prototypes from APTPCB can be produced in as little as 24 hours. Production runs typically take 5-7 days depending on volume and surface finish requirements.

8. Does the PCB need to be grounded to the enclosure? For metal enclosures, grounding the PCB mounting holes to the chassis helps shield against RF interference. For plastic enclosures, ensure the internal ground planes are robust.

9. How does humidity affect the PCB design? High humidity can cause surface leakage. Aside from conformal coating, increasing the spacing between high-voltage and sensitive analog traces helps mitigate this.

10. Can I use a CO2 Sensor PCB design for SO2? Usually not directly. CO2 Sensor PCBs typically use NDIR (optical) technology, which requires high current pulses for the IR lamp, whereas SO2 sensors are usually electrochemical. The drive circuitry is completely different.

11. What is the best way to test the PCB without gas? Use a "dummy cell" or a precision current source to inject a known current (e.g., 100 nA) into the input. This verifies the gain and linearity of the electronics before introducing the variable of the chemical sensor.

12. Why is ENIG preferred over HASL? HASL (Hot Air Solder Leveling) leaves an uneven surface, which can cause the sensor socket to sit at an angle. ENIG is perfectly flat and offers better contact resistance for the socket pins over time.

13. Do I need a dedicated ADC? The internal ADCs of modern microcontrollers (12-bit or 16-bit) are often sufficient if the analog front-end is well designed. For ppb-level detection, an external 24-bit Sigma-Delta ADC is recommended.

Related pages & tools

- PCB Manufacturing Services – Full-spec fabrication for industrial sensor boards.

- DFM Guidelines – Ensure your sensor layout meets manufacturing constraints.

- Teflon PCB Materials – High-performance substrates for ultra-low leakage requirements.

- Get a Quote – Instant pricing for your sensor PCB project.

Glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Electrochemical Cell | A sensor device that converts gas concentration into an electrical current via chemical reaction. |

| TIA (Transimpedance Amplifier) | An op-amp circuit that converts the tiny current output of the sensor into a usable voltage. |

| Working Electrode (WE) | The electrode where the gas oxidation/reduction occurs, generating the signal current. |

| Reference Electrode (RE) | Maintains a stable potential to ensure the reaction at the Working Electrode is controlled. |

| Counter Electrode (CE) | Completes the circuit, balancing the current generated at the Working Electrode. |

| Guard Ring | A copper trace surrounding a sensitive node, driven to the same potential to block leakage current. |

| Cross-Sensitivity | The response of the sensor to a gas other than the target gas (e.g., SO2 sensor responding to CO). |

| Zero Drift | The change in the sensor's baseline output over time or temperature when no gas is present. |

| Span Drift | The change in sensitivity (slope) of the sensor over time. |

| Potentiostat | The electronic circuit required to bias and read a 3-electrode electrochemical sensor. |

| ppb / ppm | Parts per billion / Parts per million; units of gas concentration measurement. |

| Bias Voltage | A specific voltage applied between the Reference and Working electrodes to activate the sensor. |

Conclusion

Designing an SO2 Sensor PCB is an exercise in precision. The difference between a functional safety device and a noisy failure often lies in the details: the quality of the surface finish, the implementation of guard rings, and the cleanliness of the assembly process. By adhering to strict layout rules and selecting the right materials, engineers can ensure their detection systems perform reliably in critical environments.

Whether you are prototyping a new multi-gas detector or scaling up production for industrial scrubbers, APTPCB provides the manufacturing expertise required for high-reliability sensor PCBs. From selecting the right ENIG finish to ensuring strict impedance control where necessary, we help you transition from design to deployment with confidence.