Key Takeaways

- Definition: A Software Validation PCB is a hardware platform specifically designed or designated to verify embedded firmware, operating systems, and application software before mass production.

- Role: It acts as the "stable truth" in the development cycle; if the hardware is flawless, any errors found can be attributed to the code.

- Critical Metrics: Signal integrity, power stability, and test point accessibility are the top performance indicators.

- Medical Context: In regulated industries, these boards often must meet safety standards like 2 MOOP PCB (Means of Operator Protection) or 2 MOPP PCB (Means of Patient Protection) to validate safety-critical software.

- Common Pitfall: Removing debug headers or test points too early in the design revision process, making software validation impossible during DVT (Design Validation Test).

- Validation: Requires a mix of automated ICT (In-Circuit Test) and functional testing (FCT) to ensure the board is ready for code injection.

What Software Validation PCB really means (scope & boundaries)

To understand how to manufacture a board fit for testing code, we must first define the scope of a Software Validation PCB.

In the electronics manufacturing ecosystem, hardware and software are often developed in parallel. A Software Validation PCB is not necessarily the final commercial product. Instead, it is a version of the hardware—often an Engineering Validation Test (EVT) or Design Validation Test (DVT) unit—optimized to stress-test the firmware.

At APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory), we distinguish these boards from standard production units by their specific requirements for accessibility and robustness. While a final consumer product might prioritize miniaturization, a Software Validation PCB prioritizes observability. It allows developers to hook up logic analyzers, oscilloscopes, and debuggers to trace execution paths.

The scope of this term covers three distinct hardware types:

- Evaluation Boards (EVB): Early-stage PCBs used to validate the feasibility of the main processor or sensor drivers.

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Cards: PCBs designed to simulate inputs and outputs for the main controller, tricking the software into thinking it is operating in a real-world environment (e.g., an automotive ECU test rig).

- Pre-production Units: Near-final hardware used for regression testing, long-duration stability tests, and certification.

If the PCB itself has impedance mismatches, poor grounding, or unstable power rails, software engineers will waste weeks debugging "ghost" errors that are actually hardware artifacts. Therefore, the manufacturing quality of a Software Validation PCB is often higher or more strictly controlled than low-cost mass production consumer goods.

Software Validation PCB metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once the scope is defined, the next step is understanding the quantitative metrics that define a high-quality validation board.

A Software Validation PCB must provide a deterministic environment. If the voltage sags when the processor ramps up, the software might trigger a brown-out reset, which looks like a code crash. To prevent this, we track specific metrics during fabrication and assembly.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical range or influencing factors | How to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Distribution Network (PDN) Impedance | Ensures stable voltage delivery during high current transients (e.g., CPU waking up). | Target < 10 mΩ - 100 mΩ depending on frequency. | Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) or simulation. |

| Signal Integrity (Eye Diagram) | Poor signal quality causes bit errors in memory or communication, leading to software corruption. | Eye opening > 80% of unit interval; Jitter < 5%. | Oscilloscope with high-speed probes. |

| Test Point Coverage | Software teams need physical access to signals to verify logic states. | > 90% of active nets accessible via pads or headers. | CAD review (DFT analysis). |

| Thermal Stability (Tg) | Overheating causes throttling, which alters software timing and performance. | Tg > 170°C for high-performance computing boards. | Thermal cycling test / IR camera. |

| Dielectric Constant (Dk) Stability | Variations in Dk affect signal timing, potentially breaking high-speed driver code. | Tolerance ± 5% or better (e.g., Rogers or Panasonic materials). | TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry). |

| Safety Isolation (Medical) | For medical software, hardware must prove isolation to validate safety routines. | Compliance with 2 MOPP PCB (4000 VAC isolation). | Hi-Pot Testing (Dielectric Withstand). |

How to choose Software Validation PCB: selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

Understanding the metrics leads directly to making the right choices based on your specific development scenario. Not all validation boards need gold-plated connectors or high-frequency laminates.

Here is how to choose the right Software Validation PCB configuration based on your project needs.

Scenario 1: Early Firmware Development (The "Breakout" Board)

Goal: Basic driver development and bringing up the MCU.

- Recommendation: Use a larger form factor than the final product. Break out every GPIO pin to standard 2.54mm headers.

- Trade-off: The board will be physically large and have poor RF performance due to long traces, but it offers maximum debug capability.

- APTPCB Tip: Prioritize NPI small batch PCB manufacturing speed over tight tolerances here.

Scenario 2: High-Speed Interface Validation (DDR, PCIe, Ethernet)

Goal: Validating that the OS can handle high data throughput without crashing.

- Recommendation: Use controlled impedance materials (Isola or Megtron). Minimize vias on high-speed lines.

- Trade-off: Higher material cost and longer lead time. You cannot use standard FR4 if you are validating 10Gbps interfaces.

- Key Feature: Back-drilling may be required to remove stubs that cause signal reflection.

Scenario 3: Medical Device Software Validation (Safety Critical)

Goal: Validating software that controls patient-contact parts (e.g., infusion pumps).

- Recommendation: The PCB must physically implement safety barriers. You must specify 2 MOPP PCB (Means of Patient Protection) spacing rules (typically 8mm creepage) or 2 MOOP PCB (Means of Operator Protection) depending on the user.

- Trade-off: Layout density decreases significantly. The software validation is invalid if the hardware doesn't meet IEC 60601-1 because the device is illegal to sell.

- Reference: See our capabilities in Medical PCB for isolation details.

Scenario 4: Environmental Stress Screening (ESS)

Goal: Validating software behavior under extreme heat or vibration.

- Recommendation: Use High-Tg FR4 and heavy copper. Ensure component footprints are slightly larger for stronger solder joints.

- Trade-off: The board is more robust than the final consumer version, which might mask mechanical failures, but it ensures the software can be tested until the code breaks, not the board.

Scenario 5: Automated Regression Testing Farms

Goal: Racks of 100+ boards running automated scripts 24/7.

- Recommendation: Focus on durability of connectors (USB/UART). Use hard gold plating on edge connectors.

- Trade-off: Higher plating cost.

- Why: If the USB port wears out after 500 cycles, the automated test fails, and developers waste time investigating a "software bug" that is actually a broken connector.

Scenario 6: Wireless/RF Stack Validation

Goal: Tuning antenna firmware and Bluetooth/Wi-Fi stacks.

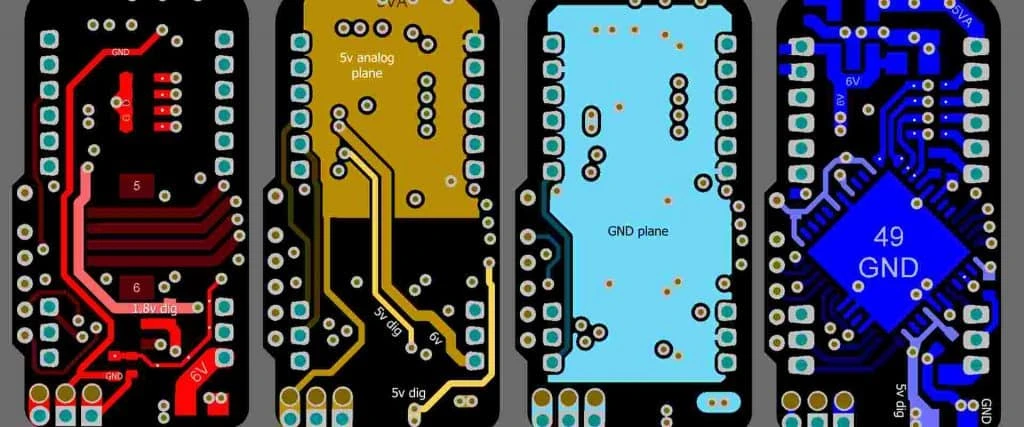

- Recommendation: 4-layer minimum with a solid ground plane. RF sections must be shielded.

- Trade-off: Requires specialized RF testing during manufacturing to ensure the board is identical to the simulation.

Software Validation PCB implementation checkpoints (design to manufacturing)

After selecting the right scenario, the actual execution moves from design files to the factory floor. This section outlines the critical checkpoints to ensure the Software Validation PCB performs as intended.

Phase 1: Design & Layout

- Debug Header Placement: Ensure JTAG/SWD headers are placed away from tall components so clips can be attached easily.

- Test Point Strategy: Add test points for all power rails and critical interrupt lines. Do not rely on probing component legs (risk of shorting).

- Silkscreen Clarity: Label every connector, LED, and switch clearly. Software engineers often work with the schematic closed; the board should be self-documenting.

- Strap Options: Use 0-ohm resistors or DIP switches to allow hardware configuration changes (e.g., boot mode selection) without soldering.

Phase 2: Fabrication (Bare Board)

- Impedance Coupon Test: Verify that the calculated impedance matches the manufactured reality. If the impedance is off, high-speed software drivers will fail unpredictably.

- Plating Thickness: Ensure sufficient copper in via barrels. Validation boards undergo thermal stress; weak vias will crack, causing intermittent open circuits that look like software glitches.

- Solder Mask Definition: Use LDI (Laser Direct Imaging) for precise mask openings, especially if using fine-pitch components for the main processor.

Phase 3: Assembly (PCBA)

- IC Programming: This is the bridge between hardware and software. The bootloader must be flashed correctly.

- Check: Verify the checksum of the flashed firmware.

- Link: IC Programming services.

- X-Ray Inspection: Essential for BGAs (processors). A void in a BGA ball can cause a pin to disconnect when the board heats up, crashing the software.

- Connector Reinforcement: For validation boards, consider adding epoxy or through-hole stakes to surface-mount connectors to withstand repeated plugging.

Phase 4: Final Validation

- FCT (Functional Circuit Test): Before handing the board to the software team, run a hardware self-test.

- Action: Verify all voltage rails are within 5%.

- Link: FCT Test capabilities.

- Serialization: Every validation board must have a unique serial number (barcode/QR). Software bugs are often tied to specific hardware batches.

Software Validation PCB common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a solid plan, errors occur. Here are the most common mistakes we see at APTPCB when clients order boards for software validation.

1. Removing Test Points to Save Space

- Mistake: Designers remove test points to make the board smaller, matching the final form factor too early.

- Consequence: Software engineers cannot hook up logic analyzers to debug timing issues.

- Correction: Keep test points on EVT and DVT builds. Only remove them in the final PVT (Production Validation Test) revision if absolutely necessary.

2. Ignoring Power Integrity for "Simple" Boards

- Mistake: Assuming a simple LDO is enough for a modern MCU without proper decoupling capacitors.

- Consequence: The MCU resets during high-load software routines (e.g., writing to flash). Developers blame the flash driver, but it's a hardware brown-out.

- Correction: Simulate the PDN (Power Distribution Network) and use sufficient bulk capacitance.

3. Confusing 2 MOOP PCB with 2 MOPP PCB

- Mistake: In medical devices, using Operator Protection (MOOP) standards for a device that touches the patient.

- Consequence: The software validation is legally void because the hardware is unsafe for clinical trials.

- Correction: Always default to the stricter 2 MOPP PCB standard (4000V isolation, 8mm creepage) if there is any chance of patient contact.

4. Using Low-Quality Sockets

- Mistake: Using cheap sockets for chips that need to be swapped frequently.

- Consequence: Contact resistance increases over time, causing signal degradation and false software failures.

- Correction: Use high-quality ZIF (Zero Insertion Force) sockets or high-cycle industrial sockets.

5. Lack of Ground Points

- Mistake: Providing signal test points but no nearby ground points for the oscilloscope probe.

- Consequence: Long ground loops pick up noise, making the signal look dirty on the scope.

- Correction: Place a ground via or pad next to every major signal test point group.

6. Undocumented Rework

- Mistake: The factory or technician modifies the board (cuts a trace, adds a wire) but doesn't update the schematic.

- Consequence: Software behaves differently on different boards, leading to "works on my machine" syndrome.

- Correction: Strict revision control. Any "blue wire" fix must be documented and applied to all validation units identically.

Software Validation PCB FAQ (cost, lead time, materials, testing, acceptance criteria)

Q1: How much does a Software Validation PCB cost compared to a production board? A: Typically, the unit cost is 2-5x higher. This is due to lower volumes (NPI), faster turnaround requirements, and often more expensive features like hard gold plating or controlled impedance that might be value-engineered out of the final product.

Q2: What is the lead time for a complex validation board? A: For a standard 4-6 layer board, APTPCB can deliver in 24-48 hours. For complex HDI boards or those requiring specific 2 MOPP PCB safety materials, allow 5-8 days.

Q3: Can I use standard FR4 for all validation boards? A: Not always. If you are validating RF software or high-speed DDR memory, standard FR4 has too much signal loss. You may need materials like Rogers or Isola. For general MCU logic, standard FR4 is sufficient.

Q4: What are the acceptance criteria for a Software Validation PCB? A: Unlike mass production where "pass/fail" is enough, validation boards often require a "Certificate of Conformance" (CoC) and impedance reports. The acceptance criteria should include 100% electrical testing (flying probe) and X-ray inspection for all BGAs.

Q5: How do I validate software on a board that isn't finished yet? A: You use an FPGA prototyping board or a larger "development" version of the PCB. This version contains the target silicon but spreads components out for access.

Q6: Why is my software crashing only on the battery-powered version of the PCB? A: This is usually a high internal resistance (ESR) issue in the battery path or poor DC-DC converter response. The validation PCB should be tested with a power supply that simulates a dying battery to validate the software's low-power handling.

Q7: What is the difference between EVT and DVT for software validation? A: EVT (Engineering Validation) boards focus on "does it turn on?" and basic drivers. DVT (Design Validation) boards are "production intent" and are used to validate the full software stack, including edge cases and regulatory compliance.

Q8: How does "2 MOOP PCB" compliance affect software? A: Indirectly. If the isolation barrier (MOOP) is breached by a layout error, the high voltage noise can jump to the logic side, crashing the processor. Robust isolation ensures the software runs in a clean electromagnetic environment.

Resources for Software Validation PCB (related pages and tools)

To further assist in your project, we have curated a list of internal tools and resources relevant to validation hardware.

- Design for Manufacturing: Before finalizing your validation board, run it through our DFM Guidelines to ensure it can be built reliably.

- Impedance Calculation: Use our Impedance Calculator to design the stackup for high-speed signals.

- Visual Inspection: Use the Gerber Viewer to double-check test point placement before ordering.

- Assembly Services: Learn about our Turnkey Assembly to get fully populated boards ready for software loading.

Software Validation PCB glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| DUT (Device Under Test) | The specific component or board being tested by the software/hardware setup. |

| EVT (Engineering Validation Test) | The first prototype stage; boards are used for bringing up the operating system and basic drivers. |

| DVT (Design Validation Test) | The second stage; boards are production-quality and used for full software regression testing. |

| JTAG (Joint Test Action Group) | A standard interface for debugging embedded systems and programming chips. |

| SWD (Serial Wire Debug) | A 2-pin alternative to JTAG, common in ARM Cortex microcontrollers. |

| 2 MOPP PCB | Two Means of Patient Protection. A safety standard requiring specific isolation (4000V) for medical devices. |

| 2 MOOP PCB | Two Means of Operator Protection. Similar to MOPP but protects the user/operator, not the patient (3000V). |

| HIL (Hardware-in-the-Loop) | A simulation technique where the PCB thinks it is in a car/plane, but inputs are generated by a computer. |

| Test Point | A dedicated pad on the PCB designed to be probed by an oscilloscope or pogo pin. |

| Firmware | Low-level software embedded in the hardware (e.g., BIOS, bootloader). |

| ICT (In-Circuit Test) | A test method that checks for shorts, opens, and component values using a "bed of nails" fixture. |

| FCT (Functional Circuit Test) | A test that powers up the board and runs a script to verify it actually works (e.g., "blink LED"). |

Conclusion (next steps)

A Software Validation PCB is more than just a circuit board; it is the foundation upon which your entire software investment rests. If the foundation is shaky—plagued by noise, poor soldering, or inadequate access—your software team will spend months chasing ghosts instead of features.

Whether you are building a rugged industrial controller, a high-speed data server, or a medical device requiring 2 MOPP PCB compliance, the manufacturing quality of your validation hardware is non-negotiable.

Ready to build your validation units? When requesting a quote from APTPCB, please provide:

- Gerber Files: Including all copper layers and drill files.

- Stackup Requirements: Specify any controlled impedance lines (e.g., 50Ω single-ended, 100Ω differential).

- Test Requirements: Indicate if you need FCT or IC programming performed at the factory.

- Volume: Specify if this is an NPI run (5-50 units) or a larger pilot run.

By prioritizing robust hardware design and partnering with a capable manufacturer, you ensure that when your software fails, it’s a bug in the code—not a flaw in the board.