Key Takeaways

- Definition Scope: A Studio Monitor PCB is the central circuit board governing signal amplification, crossover logic, and power distribution in professional audio reference speakers.

- Signal Integrity: The primary goal is maintaining audio transparency; poor layout leads to Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and noise floor issues.

- Material Matters: While FR4 is standard, high-frequency digital inputs may require specialized substrates to prevent jitter.

- Thermal Management: Active monitors generate significant heat; the PCB design must integrate with heatsinks and airflow strategies.

- Validation: Electrical testing is not enough; acoustic measurement and burn-in testing are mandatory for professional certification.

- Manufacturing Partner: Working with an experienced manufacturer like APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory) ensures that design intent translates to physical reliability.

What Studio Monitor PCB really means (scope & boundaries)

To understand the engineering challenges behind professional audio, we must first define the specific role of the printed circuit board within the enclosure.

A Studio Monitor PCB is not merely a generic amplifier board; it is a precision instrument designed to deliver flat frequency response and minimal coloration. Unlike consumer audio equipment, which may enhance bass or treble to sound "pleasing," a studio monitor must reveal the truth of the recording. The PCB is the foundation of this transparency. It connects the input stage, the active crossover network, the power amplifiers, and the protection circuits.

In modern production environments, the scope of these boards has expanded. A Radio Studio PCB often integrates shielding against high RF interference found in broadcast towers. Similarly, a TV Studio PCB must account for video sync signals and lip-sync latency requirements. The complexity increases further with digital monitors, where a Studio Interface PCB handles AES/EBU or Dante network inputs before converting them to analog signals for the drivers.

The distinction between a standard PCB and a monitor-grade PCB lies in the tolerance of components and the layout strategy. Trace routing must minimize crosstalk between the high-current power section and the sensitive low-voltage input section. Grounding strategies are critical to eliminate the "hum" that can ruin a mix. Whether it is a Modulation Monitor PCB used to analyze signal strength or the main driver board in a near-field monitor, the engineering priority remains the same: absolute signal fidelity.

Metrics that matter (how to evaluate quality)

Once you understand the scope of the board's function, you must establish quantifiable metrics to evaluate its performance before and after manufacturing.

In the world of high-fidelity audio, vague terms like "warmth" or "punch" are not actionable for PCB designers. We rely on electrical specifications that directly correlate to audio performance. A board that fails these metrics will result in a monitor that fatigues the listener or hides mix details.

| Metric | Why it matters | Typical range or influencing factors | How to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Harmonic Distortion + Noise (THD+N) | Indicates how much the PCB adds unwanted artifacts to the original signal. | Target: < 0.001% for high-end monitors. Influenced by layout grounding and component quality. | Audio Analyzer (inject sine wave, measure output spectrum). |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Determines the "quietness" of the monitor when no audio is playing (hiss level). | Target: > 100dB. Influenced by trace width, shielding, and power supply isolation. | Measure noise floor voltage relative to nominal output level. |

| Crosstalk | Measures signal leakage between Left/Right channels or High/Low frequency bands. | Target: < -90dB. Influenced by trace spacing and ground pours. | Drive one channel/band, measure leakage in the idle channel/band. |

| Damping Factor | Affects the amplifier's ability to control the speaker cone motion (tight bass). | Target: > 200. Influenced by output trace thickness (impedance) and connector quality. | Calculate ratio of load impedance to source impedance. |

| Thermal Resistance (Rth) | Critical for active monitors where amps are built-in; prevents overheating. | Lower is better. Influenced by copper weight (2oz vs 1oz) and thermal vias. | Thermal imaging during load testing. |

| Impedance Control | Vital for digital inputs (AES/EBU, USB) to prevent data reflection and jitter. | Typically 90Ω or 100Ω differential pairs. | Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) or use an Impedance Calculator. |

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Ensures the PCB does not warp under the heat of Class A/B amplifiers. | Standard: 130°C. High Performance: 170°C (High Tg FR4). | Material datasheet verification. |

Selection guidance by scenario (trade-offs)

Metrics inform which board configuration fits your specific environment, but different applications require prioritizing different features.

There is no "one size fits all" Studio Monitor PCB. A board designed for a massive main monitor in a mastering suite has different requirements than a portable reference monitor for a broadcast van. Making the right choice involves balancing cost, thermal performance, and signal integrity.

Scenario 1: The Active Near-Field Monitor

- Context: The standard workhorse for music production, sitting 1-2 meters from the engineer.

- Priority: Thermal management and compact integration.

- Trade-off: Because the PCB is inside the cabinet, vibration is a major issue.

- Recommendation: Use FR4 with a high Tg (170°C). Implement heavy copper (2oz) for power rails to act as a heat spreader. Secure large capacitors with silicone to prevent vibration fatigue.

Scenario 2: The Mastering Grade Main Monitor

- Context: Large, full-range systems used for final quality control.

- Priority: Absolute lowest THD and highest dynamic range.

- Trade-off: Cost and size are secondary.

- Recommendation: Separate the power supply PCB from the audio signal PCB. Use 4-layer or 6-layer boards to dedicate internal planes to ground and power, maximizing shielding. Use gold plating (ENIG) for better conductivity and oxidation resistance over decades.

Scenario 3: The Broadcast Modulation Monitor

- Context: A Modulation Monitor PCB is used in radio stations to ensure transmission levels are legal and clear.

- Priority: RF immunity and reliability.

- Trade-off: Audio "sweetness" is less important than measurement accuracy.

- Recommendation: Extensive shielding cans are required. The layout must strictly separate RF sections from AF (Audio Frequency) sections. Use surface mount technology (SMT) to minimize lead inductance.

Scenario 4: The Digital Input Monitor

- Context: Monitors that accept USB, AES/EBU, or Dante directly.

- Priority: Mixed-signal integrity.

- Trade-off: Digital noise can bleed into the analog amplification stage.

- Recommendation: This requires a Studio Interface PCB design approach. Use a 4-layer stackup minimum. Place the DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter) as close to the analog amp input as possible but isolate the ground planes with a "star ground" or net-tie point.

Scenario 5: The Portable/Field Monitor

- Context: Used in OB (Outside Broadcast) vans or location recording.

- Priority: Physical durability and power efficiency.

- Trade-off: Lower power output to conserve battery/heat.

- Recommendation: Class D amplifier topology is essential here. The PCB must be thick (1.6mm or 2.0mm) to resist flexing during transport. Conformal coating may be necessary if used in humid environments.

Scenario 6: The Budget/Entry-Level Monitor

- Context: Home studio equipment.

- Priority: Cost reduction without sacrificing basic functionality.

- Trade-off: Higher noise floor and lower damping factor.

- Recommendation: Single-sided or simple double-sided PCB. Use HASL finish instead of ENIG. Combine power and signal on one board but maintain physical distance between the transformer and input stage.

From design to manufacturing (implementation checkpoints)

After selecting the type of board and understanding the trade-offs, the focus shifts to the rigorous manufacturing workflow required for professional audio.

Designing a Studio Monitor PCB is only half the battle; executing that design requires a disciplined manufacturing process. At APTPCB, we see many designs that look good in software but fail in the real world due to manufacturing oversights. Follow these checkpoints to ensure success.

1. Schematic Capture & Component Selection

- Action: Select audio-grade capacitors (e.g., polypropylene) for signal paths. Choose low-noise op-amps.

- Risk: Using general-purpose ceramic capacitors in the audio path can introduce microphonic noise (piezoelectric effect).

- Acceptance: BOM review confirming component dielectrics and tolerances.

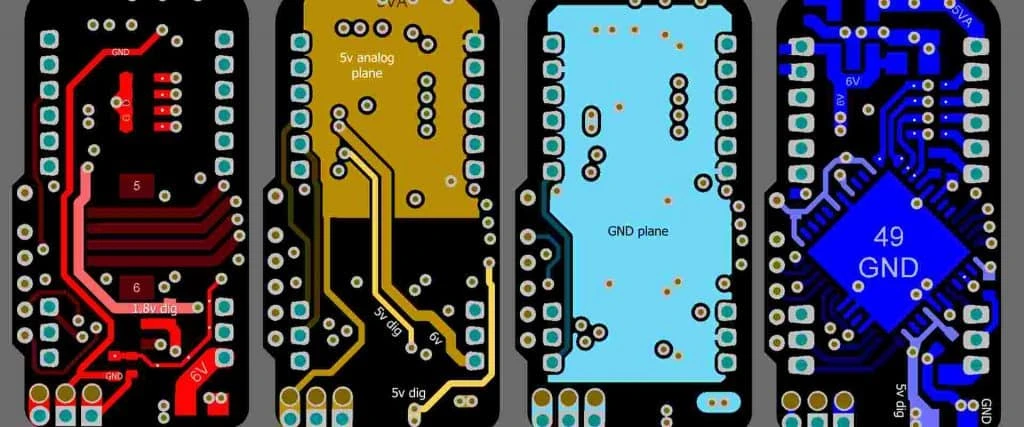

2. Stackup Design

- Action: Define the layer stack. For professional monitors, a 4-layer board (Signal-Ground-Power-Signal) is standard.

- Risk: 2-layer boards often struggle with ground loops in active monitor designs.

- Acceptance: Verify impedance calculations for any digital traces.

3. Layout: The Star Ground

- Action: Implement a "Star Ground" topology where all ground points meet at the power supply filter caps.

- Risk: Daisy-chaining grounds creates voltage potential differences, resulting in the dreaded 60Hz/50Hz hum.

- Acceptance: Visual inspection of the Gerber files focusing on the ground net.

4. Power Trace Sizing

- Action: Calculate trace width based on the peak current of the amplifier, not the average.

- Risk: Thin traces increase resistance, lowering the damping factor and causing voltage sag during bass drops.

- Acceptance: Current density simulation.

5. DFM Review (Design for Manufacturing)

- Action: Submit files for a DFM check before production. This checks for acid traps, slivers, and drill tolerance.

- Risk: Unmanufacturable features delay production or cause field failures.

- Acceptance: Green light from the manufacturer's engineering team. (See our DFM guidelines).

6. Surface Finish Selection

- Action: Choose ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) for flat pads and corrosion resistance.

- Risk: HASL (Hot Air Solder Leveling) surfaces can be uneven, causing issues with fine-pitch components like DSP chips.

- Acceptance: Specification on the fabrication drawing.

7. Prototype Assembly (PCBA)

- Action: Assemble a small batch (5-10 units) for validation.

- Risk: Committing to mass production without testing the physical board often leads to costly scrap.

- Acceptance: Physical fit check inside the speaker cabinet.

8. In-Circuit Testing (ICT)

- Action: Use a bed-of-nails fixture to test for shorts, opens, and component values.

- Risk: Manual testing is too slow and unreliable for volume production.

- Acceptance: 100% pass rate on electrical continuity.

9. Audio Performance Validation

- Action: Run the assembled PCB through an Audio Precision analyzer.

- Risk: A board can pass electrical checks but fail audio specs due to bad solder joints or counterfeit parts.

- Acceptance: THD+N and SNR within defined limits.

10. Burn-In Testing

- Action: Run the amplifier at high power for 24-48 hours.

- Risk: Infant mortality of components usually happens in the first few hours of thermal stress.

- Acceptance: No thermal shutdowns or component failures.

11. Final Integration Check

- Action: Install the PCB into the final cabinet and test acoustically.

- Risk: Mechanical resonance from the PCB can cause rattles.

- Acceptance: Sweep test ensuring no mechanical buzz.

Common mistakes (and the correct approach)

Even with a solid plan and a checklist, specific errors can ruin audio performance if they are not actively avoided.

Over years of fabricating audio boards, we have identified recurring patterns of failure. Avoiding these pitfalls distinguishes a hobbyist project from a professional product.

Neglecting the Return Path:

- Mistake: Thinking of signals as one-way streets. Current must return to the source.

- Correction: Always visualize the return current path. If it has to take a long detour around a split plane, it creates a loop antenna that picks up noise.

Placing Analog and Digital Too Close:

- Mistake: Routing the PWM switching lines of a Class D amp next to the sensitive input pre-amp traces.

- Correction: Physical separation is the best filter. Keep high-voltage switching and low-voltage analog on opposite sides of the board or shielded by a ground fence.

Ignoring Thermal Expansion:

- Mistake: Bolting a large power transistor to the chassis and soldering it rigidly to the PCB.

- Correction: As the chassis heats up, it expands. If the connection is rigid, solder joints will crack. Use flexible leads or strain-relief bends in the component legs.

Poor Connector Placement:

- Mistake: Placing input connectors far from the input circuitry, requiring long internal cables.

- Correction: Design the Studio Interface PCB so connectors mount directly to the board, minimizing wire length and acting as a Faraday cage entry point.

Overlooking Copper Weight:

- Mistake: Using standard 1oz copper for a 200W amplifier.

- Correction: High-power monitors need 2oz or even 3oz copper to handle current without heating up the traces themselves.

Confusing Chassis Ground with Signal Ground:

- Mistake: Connecting signal ground to the metal chassis at multiple points.

- Correction: Connect signal ground to chassis ground at exactly one point (usually near the input jack) to prevent ground loops.

Using the Wrong Capacitor Dielectric:

- Mistake: Using Class 2 ceramic capacitors (like X7R) in the audio signal path.

- Correction: Use C0G/NP0 ceramics or film capacitors. X7R capacitors change capacitance with voltage, causing distortion.

Forgetting Mounting Holes:

- Mistake: Designing the circuit perfectly but forgetting to add plated mounting holes for grounding the PCB to the chassis.

- Correction: Include mounting holes early in the layout phase and define which ones are connected to ground.

FAQ

Avoiding mistakes often leads to specific technical questions regarding materials and costs. Here are the most common inquiries we receive about Studio Monitor PCB manufacturing.

Q: Can I use standard FR4 for a high-end Studio Monitor PCB? A: Yes, standard FR4 is sufficient for most analog audio applications. However, for Class D amplifiers or digital interface boards, High-Tg FR4 is recommended to handle heat, and controlled dielectric materials may be needed for high-speed digital inputs.

Q: What is the best copper thickness for audio PCBs? A: For line-level signal processing (pre-amps, crossovers), 1oz (35µm) is standard. For power amplifier stages, 2oz (70µm) is preferred to reduce resistance and improve the damping factor.

Q: Should I use lead-free or leaded solder? A: Due to RoHS regulations, lead-free (SAC305) is the industry standard. While some audiophiles claim leaded solder sounds better, there is no scientific evidence to support this. A good solder joint depends on the process, not just the alloy.

Q: How do I prevent "pop" noises when turning the monitor on? A: This is a circuit design issue, not just a PCB issue. You need a mute circuit or a relay on the output that engages only after the power rails have stabilized. The PCB must have space allocated for this protection logic.

Q: What is the difference between a Radio Studio PCB and a regular audio PCB? A: A Radio Studio PCB operates in environments with high RF energy (transmitters). It requires aggressive shielding, ferrite beads on inputs, and specific layout techniques to reject RF interference that regular audio boards might not need.

Q: Why is the color of the solder mask important? A: Technically, it isn't for performance. However, Matte Black or Matte Green is often preferred in studio gear to prevent internal light reflections if the equipment has vents, and it aids in automated optical inspection (AOI) contrast.

Q: How much does it cost to manufacture a custom monitor PCB? A: Cost depends on size, layer count, and quantity. A 4-layer prototype batch might cost $100-$200, while mass production drops the unit price significantly. Use our PCB manufacturing services page to get a precise estimate.

Q: Do I need gold plating (ENIG)? A: For professional gear, yes. ENIG ensures flat pads for fine-pitch components and does not oxidize over time like OSP or HASL, ensuring the monitor lasts for decades.

Q: What files do I need to send for manufacturing? A: You need to send Gerber files (RS-274X), a Drill file (NC Drill), a Pick and Place file (centroid), and a BOM (Bill of Materials) if you require assembly.

Q: Can APTPCB help with the layout design? A: We specialize in manufacturing and assembly. While we provide DFM feedback to improve your design, the initial circuit design and layout should be done by an audio engineer.

Related pages & tools

For deeper technical details and to verify your design parameters, explore our specific tools and guides.

- DFM Guidelines: A comprehensive checklist to ensure your audio PCB design is manufacturable without errors or delays.

- PCB Manufacturing Services: Detailed capabilities regarding layer counts, copper weights, and material options available at APTPCB.

Glossary (key terms)

To communicate effectively with manufacturers and engineers, use standard terminology.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Active Crossover | A circuit that splits the audio signal into frequency bands (Low, Mid, High) before amplification. |

| BOM (Bill of Materials) | A comprehensive list of all components (resistors, caps, chips) required to assemble the PCB. |

| Class D Amplifier | A highly efficient amplifier topology often used in monitors; requires careful PCB layout to manage EMI. |

| Crosstalk | The unwanted transfer of signals between communication channels (e.g., Left channel bleeding into Right). |

| Damping Factor | The ratio of load impedance to source impedance; indicates how well the amp controls the speaker. |

| DFM (Design for Manufacturing) | The practice of designing PCBs in a way that makes them easy and cheap to manufacture. |

| EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) | Electrical noise from external sources that can degrade audio quality. |

| ENIG | Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold; a high-quality surface finish for PCBs. |

| Ground Loop | A circular current path in the ground system that picks up interference (hum). |

| Gerber Files | The standard file format used to describe PCB images (copper layers, solder mask, etc.) to the manufacturer. |

| Modulation Monitor | A device used in broadcasting to measure the modulation level of the transmitted signal. |

| Near-Field | Studio monitors designed to be listened to from a short distance (1-2 meters) to minimize room acoustics. |

| PCB Stackup | The arrangement of copper layers and insulating material in a multi-layer PCB. |

| SNR (Signal-to-Noise Ratio) | A measure of signal strength relative to background noise. |

| Star Ground | A grounding technique where all ground paths connect to a single point to prevent loops. |

| THD+N | Total Harmonic Distortion plus Noise; a key metric for audio fidelity. |

| Via | A plated hole that allows electrical connection between different layers of a PCB. |

Conclusion (next steps)

Understanding terms, metrics, and processes prepares you for the final step: moving from a digital file to a physical product.

A Studio Monitor PCB is the silent partner in audio production. It doesn't make sound itself, but it dictates the quality of the sound that is produced. Whether you are building a Radio Studio PCB for a broadcast tower or a high-fidelity crossover for a mastering suite, the principles of signal integrity, thermal management, and robust manufacturing remain constant.

To ensure your design meets the rigorous standards of the audio industry, you need a manufacturing partner who understands these nuances. APTPCB has the experience and equipment to handle complex stackups, heavy copper requirements, and strict tolerance assembly.

Ready to manufacture your audio PCB? Before you submit your order, ensure you have the following ready:

- Gerber Files: Including all copper layers, solder mask, and silkscreen.

- Stackup Specifications: Define your material (FR4, High-Tg) and copper weight (1oz, 2oz).

- BOM: If you need assembly, provide a detailed bill of materials with manufacturer part numbers.

- Test Requirements: Specify if you need ICT or functional testing.

Visit our Quote Page today to upload your files and get a DFM review started. Let's build a monitor that reveals the truth of the music.