Achieving precise Wearable patch PCB impedance control is the defining challenge for modern medical and fitness devices. Unlike rigid boards, wearable patches must maintain signal integrity while flexing, adhering to the skin, and operating on ultra-thin dielectrics. Whether you are routing a 50Ω Bluetooth antenna or a 90Ω USB differential pair, the physical constraints of flexible materials (FPC) introduce variables that standard rigid PCB calculators often miss. This guide provides the engineering specifications, failure analysis, and manufacturing steps necessary to ensure your wearable patch performs reliably in the field.

Quick Answer (30 seconds)

For successful Wearable patch PCB impedance control, engineers must account for dynamic bending and material properties unique to flex circuits.

- Target Impedance: Standard single-ended traces usually require 50Ω ±10%; differential pairs often need 90Ω or 100Ω ±10%.

- Material Impact: Polyimide (PI) dielectrics are thin (often 12µm to 50µm), requiring narrower trace widths to hit impedance targets compared to FR4.

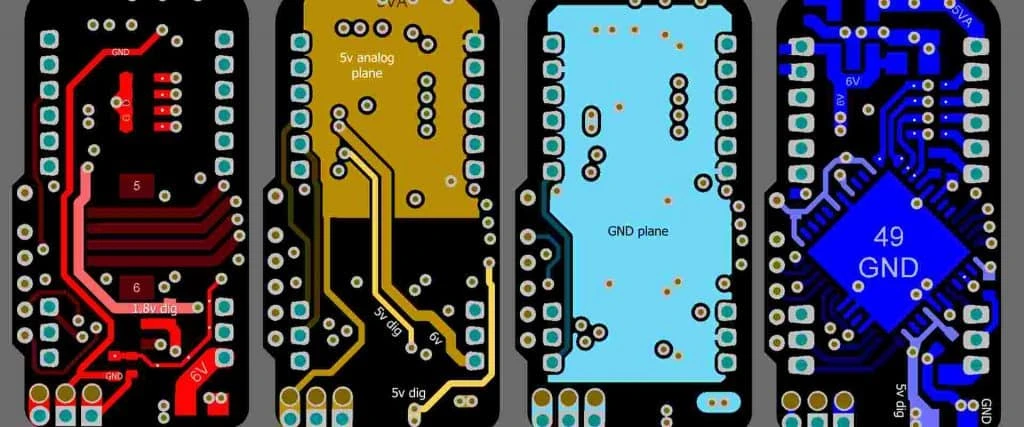

- Ground Reference: Use cross-hatched ground planes instead of solid copper to maintain flexibility; this increases impedance by 5–10% compared to solid planes.

- Coverlay Factor: The adhesive and Kapton coverlay pressed over traces will lower impedance by 2–5Ω; this must be modeled in the stackup.

- Bending Radius: Impedance changes during flexing; avoid routing controlled impedance lines in dynamic bend areas (hinges).

- Validation: Specify Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) coupons on the manufacturing panel to verify impedance before assembly.

When Wearable patch PCB impedance control applies (and when it doesn’t)

Understanding when to enforce strict impedance rules helps balance cost and performance. Not every trace on a wearable patch requires controlled impedance.

Applies (Strict Control Required):

- RF/Wireless Communication: Bluetooth (BLE), Wi-Fi, or NFC antennas and feedlines require exact 50Ω matching to prevent signal loss.

- High-Speed Data Interfaces: USB, MIPI, or LVDS lines transferring sensor data to a main controller.

- Analog Front Ends (AFE): Sensitive bio-signal lines (ECG, EEG) where mismatch causes noise reflection and signal degradation.

- Long Trace Runs: If the trace length exceeds 1/10th of the signal wavelength (critical frequency), transmission line effects apply.

- Dynamic Flex Applications: When the device actively bends during use, consistent impedance minimizes signal distortion.

Doesn’t Apply (Standard Tolerances Sufficient):

- Low-Speed Digital I/O: GPIOs for buttons, LEDs, or simple status indicators do not need impedance control.

- Power Traces: VCC and GND lines prioritize low resistance (DC drop) over AC impedance.

- Static DC Signals: Thermistor or battery voltage sensing lines.

- Short Interconnects: Traces shorter than 5mm on low-frequency circuits typically do not exhibit transmission line behavior.

- Cost-Sensitive Disposable Patches: If the device is a simple logger with no RF transmission (data read via pads later), standard tolerances may suffice.

Rules & specifications

The following table outlines the critical parameters for Wearable patch PCB impedance control. These rules ensure that the design intent survives the manufacturing process at APTPCB (APTPCB PCB Factory).

| Rule | Recommended Value/Range | Why it matters | How to verify | If ignored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trace Width Tolerance | ±15µm or ±10% (whichever is tighter) | Flex etching is sensitive; variations directly alter impedance ($Z_0$). | Optical inspection (AOI) or cross-section. | Impedance mismatch; signal reflection. |

| Dielectric Thickness | 25µm or 50µm (common PI cores) | Thinner dielectrics force very narrow traces to maintain $Z_0$. | Stackup report from fab house. | Impossible to route manufacturable trace widths. |

| Copper Weight | 1/3 oz (12µm) or 1/2 oz (18µm) | Thicker copper cracks during bending; thinner copper has higher resistance. | Micro-section analysis. | Cracking (too thick) or high loss (too thin). |

| Ground Plane Style | Cross-hatch (Mesh) | Solid copper stiffens the patch; hatch allows flexibility. | Visual check in Gerber viewer. | Patch peels off skin; solder joints crack. |

| Hatch Pitch/Width | 0.5mm pitch / 0.15mm line | Affects reference plane continuity and return path inductance. | CAM simulation tools. | EMI issues; inconsistent impedance. |

| Coverlay Thickness | 12.5µm to 25µm | Acts as a dielectric above the trace, lowering impedance. | Material datasheet check. | Final impedance reads lower than calculated. |

| Stiffener Clearance | >0.5mm from impedance lines | Stiffener transitions create stress points and impedance discontinuities. | 3D CAD review. | Signal reflection at rigid-flex transition. |

| Bend Radius Ratio | >10x thickness (Static), >20x (Dynamic) | Tight bends change the cross-sectional geometry of the trace. | Mechanical stress simulation. | Trace fracture; impedance drift during use. |

| Return Path Vias | <2.5mm spacing (ground stitching) | Ensures return current follows the signal path closely on multi-layer flex. | DRC in layout software. | High crosstalk; radiated emissions. |

| Surface Finish | ENIG or ENEPIG | Smooth surface for skin contact; consistent plating thickness. | X-ray fluorescence (XRF). | Poor solderability; skin irritation (if exposed). |

| Antenna Clearance | >1mm from body/skin | Human body tissue loads the antenna, detuning the frequency. | RF Simulation. | Reduced wireless range; connection drops. |

Implementation steps

Follow these steps to implement robust Wearable patch PCB impedance control in your design workflow.

Define the Stackup Early

- Action: Contact APTPCB to request a verified flex stackup (e.g., 2-layer PI with coverlay).

- Key Parameter: Dielectric constant ($D_k$) of Polyimide is typically 3.2–3.4.

- Acceptance Check: Confirm the stackup supports your required trace widths (e.g., 4mil trace for 50Ω).

Calculate Impedance with Hatching

- Action: Use a solver that supports meshed ground planes. Standard solid-plane calculators will be inaccurate.

- Key Parameter: Hatch transparency (%) or mesh pitch.

- Acceptance Check: Calculated width matches manufacturer capabilities (usually >3mil).

Route Critical Signals First

- Action: Route RF and differential pairs before power or GPIOs. Keep them on a single layer if possible to avoid via transitions.

- Key Parameter: Constant reference plane (do not route over gaps in the hatch).

- Acceptance Check: No splits in the ground reference directly beneath the high-speed trace.

Apply Teardrops and Curved Routing

- Action: Use curved traces (arcs) instead of 45/90-degree corners to reduce stress concentration. Add teardrops to all pads.

- Key Parameter: Teardrop ratio (typically 1.5x pad size).

- Acceptance Check: Visual inspection for sharp corners in bend areas.

Model the Coverlay Effect

- Action: Adjust trace width to account for the coverlay pressing down between traces.

- Key Parameter: Adhesive flow (usually fills gaps >50µm).

- Acceptance Check: Simulation shows target impedance with coverlay applied.

Place Ground Stitching Vias

- Action: If using a 2-layer flex, stitch the top and bottom ground pours near signal traces.

- Key Parameter: Via spacing < $\lambda/10$ of the highest frequency.

- Acceptance Check: Return path is continuous.

Generate Manufacturing Data

- Action: Export ODB++ or Gerbers. Include an impedance table in the fabrication drawing.

- Key Parameter: Specify "Impedance Lines" clearly on a separate mechanical layer or drawing.

- Acceptance Check: Gerber Viewer confirms trace widths match design.

Prototype Validation

- Action: Order a small batch with TDR coupons.

- Key Parameter: TDR measurement report.

- Acceptance Check: Measured impedance is within ±10% of target.

Failure modes & troubleshooting

Even with good design, issues can arise. Use this table to troubleshoot Wearable patch PCB impedance control failures.

| Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Checks | Fix | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Signal Loss (Attenuation) | Trace too narrow; Copper too thin; Rough copper profile. | Check insertion loss (S21); Micro-section trace width. | Widen traces; Switch to Rolled Annealed (RA) copper. | Use low-loss coverlay; optimize width/gap. |

| Impedance Too Low (<45Ω) | Trace over-etched (too wide); Dielectric thinner than spec. | Cross-section measurement; TDR analysis. | Adjust etch compensation factor in CAM. | Tighter tolerance on dielectric thickness. |

| Impedance Too High (>55Ω) | Trace under-etched (too narrow); Coverlay not fully adhered (air gaps). | Visual inspection for air bubbles; TDR. | Improve lamination pressure; widen trace in layout. | Ensure proper adhesive flow during lamination. |

| Intermittent Signal | Cracked trace due to bending; Via fracture. | Continuity test while flexing; X-ray. | Repair impossible; redesign for flexibility. | Use curved routing; move traces to neutral axis. |

| Antenna Detuning | Proximity to skin; Stiffener material interference. | VNA measurement on-body vs. off-body. | Retune matching network for "on-body" state. | Simulate with body phantom; keep antenna away from skin. |

| EMI / Crosstalk | Weak return path; Hatch density too low. | Near-field probe scan. | Add shielding film; increase hatch density. | Use solid ground under critical RF sections if possible. |

| Solder Joint Fracture | Pad lifting due to thermal stress on flex. | Visual inspection; Pull test. | Use larger pads; add coverlay openings. | Add "anchoring spurs" to pads; use teardrops. |

Design decisions

Making the right architectural choices early simplifies Wearable patch PCB impedance control.

Hatched Ground vs. Solid Ground Hatched grounds are standard for wearable patches to ensure the PCB conforms to the body. However, hatching increases inductance and raises impedance.

- Decision: Use hatching for the bulk of the board. For ultra-critical RF lines (like the 50Ω antenna feed), use a localized solid ground plane underneath that specific segment if flexibility allows, or calculate the trace width specifically for the hatch pattern.

Rolled Annealed (RA) vs. Electro-Deposited (ED) Copper

- Decision: Always specify RA copper for dynamic wearable patches. RA copper has a horizontal grain structure that withstands bending significantly better than the vertical grain of ED copper. While ED is cheaper, it is prone to fatigue cracks which alter impedance and cause open circuits.

Stiffener Placement Stiffeners (FR4 or PI) are needed under components but create stress risers.

- Decision: Never route impedance-controlled traces across the edge of a stiffener if possible. If unavoidable, widen the trace at the transition point to add mechanical strength and accept a minor impedance discontinuity.

FAQ

Q: How does the human body affect wearable patch PCB impedance? The human body acts as a large capacitor and conductive mass. When a patch is placed on the skin, it can detune antennas and alter the effective impedance of unshielded lines.

- Design antennas for "on-body" performance, not free space.

- Use EMI shielding films to isolate high-speed lines from the body.

Q: Can I use standard FR4 impedance calculators for flex PCBs? No, standard calculators assume solid ground planes and rigid dielectrics. Flex PCBs often use hatched grounds and coverlays, which significantly alter capacitance.

- Use a calculator that supports "Mesh Ground" or "Hatch Ground" configurations.

- Consult APTPCB's Impedance Calculator or engineering support.

Q: What is the minimum trace width for 50Ω on a typical flex patch? On a standard 2-layer flex with 50µm Polyimide core, a 50Ω trace is typically around 3.5 to 4.5 mils (0.09mm - 0.11mm), depending on the hatch pattern.

- Thinner cores (25µm) require even narrower traces (2-3 mils), which are harder to manufacture.

- Always validate with the fab house stackup.

Q: How do I specify impedance control in my fabrication notes? Clear communication is key.

- List the target impedance (e.g., 50Ω SE, 90Ω Diff).

- Identify the specific layers and net classes.

- State the frequency (usually tested at TDR rise time equivalent to operation).

- Reference the specific trace width and spacing designed.

Q: Why is RA copper preferred over ED copper for impedance patches? RA (Rolled Annealed) copper is more ductile.

- It maintains physical integrity during bending.

- Cracks in ED copper change the cross-sectional area, causing impedance discontinuities before complete failure.

Q: Does the coverlay adhesive affect impedance? Yes. The adhesive has a different dielectric constant than the Polyimide film.

- During lamination, adhesive flows around the trace.

- This encapsulates the trace, increasing capacitance and lowering impedance by 2–5 ohms.

Q: What is the lead time for impedance-controlled wearable patches? Standard lead times are slightly longer than rigid boards due to the complex lamination and TDR testing process.

- Prototyping: 5–8 days.

- Production: 10–15 days.

- Check APTPCB Manufacturing Services for current timelines.

Q: Can I use silver ink printed electronics instead of copper for impedance control? Silver ink has much higher resistance than copper.

- It is difficult to achieve precise impedance control with printed ink due to surface roughness and conductivity variations.

- Etched copper flex (FPC) is superior for RF and high-speed data.

Q: How do I test impedance on a finished patch that is too small for probes? You cannot probe the active circuit easily.

- Designers add "TDR Coupons" to the waste area of the production panel.

- These coupons mimic the exact geometry of the traces on the actual board and are tested by the factory.

Q: What is the cost impact of impedance control on wearable patches? It typically adds 10–20% to the PCB cost.

- Requires TDR testing labor.

- May reduce yield if tolerances are very tight.

- Requires higher-grade materials to ensure consistency.

Related pages & tools

- PCB Manufacturing Services: Explore our capabilities for Rigid-Flex and Flexible PCBs tailored for wearables.

- DFM Guidelines: Download design rules to ensure your wearable patch is manufacturable at scale.

- Impedance Calculator: Estimate trace widths and spacing for your specific stackup before starting layout.

Glossary (key terms)

| Term | Definition | Relevance to Wearables |

|---|---|---|

| FPC | Flexible Printed Circuit. | The base technology for most wearable patches. |

| Polyimide (PI) | A high-temperature polymer used as the dielectric core in flex PCBs. | Its $D_k$ and thickness determine trace impedance. |

| Coverlay | A layer of Polyimide and adhesive laminated over traces for insulation. | Affects impedance by changing the dielectric environment around the trace. |

| Hatched Ground | A mesh pattern of copper used for ground planes instead of solid copper. | Provides flexibility but increases impedance and inductance. |

| TDR | Time Domain Reflectometry. | The method used to measure characteristic impedance of a PCB trace. |

| RA Copper | Rolled Annealed Copper. | Ductile copper foil that resists fatigue from bending. |

| Stiffener | A rigid piece of material (FR4/PI/Steel) adhered to the flex. | Provides mechanical support for connectors but creates stress points. |

| Differential Pair | Two complementary signals routed together (e.g., D+/D-). | Used for noise immunity; requires controlled differential impedance ($Z_{diff}$). |

| Skin Effect | The tendency of AC current to flow near the surface of a conductor. | Becomes critical at high frequencies; surface roughness affects loss. |

| Dielectric Constant ($D_k$) | A measure of a material's ability to store electrical energy. | A key variable in the impedance formula; varies with frequency. |

| EMI Shielding Film | A conductive film applied to the outside of the flex. | Blocks interference and prevents body proximity from detuning signals. |

| Bend Radius | The minimum radius a flex PCB can be bent without damage. | Bending tighter than this limit alters impedance and cracks copper. |

Conclusion

Mastering Wearable patch PCB impedance control requires a shift in mindset from rigid board design. You must account for the mechanical realities of flexing, the electrical impact of hatched grounds, and the proximity effects of the human body. By selecting the right materials (RA copper, Polyimide), validating your stackup early with APTPCB, and adhering to strict routing protocols, you can build wearable devices that are both comfortable for the user and electrically robust.

Whether you are prototyping a smart health monitor or scaling a fitness tracker, APTPCB provides the specialized manufacturing support needed for high-performance flexible circuits.